The Gotthard Rail Tunnels

The Gotthard Rail Tunnels

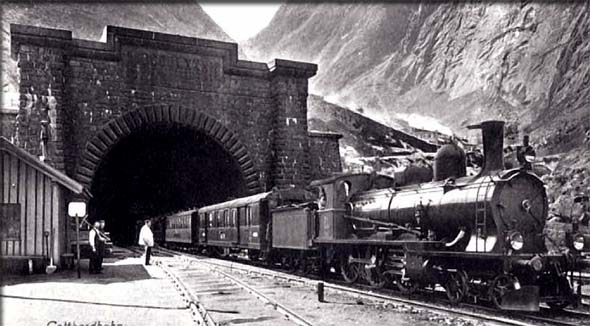

On June

1st, 2016, the longest rail tunnel in the world, the 35 ½ mile

Gotthard Base Tunnel was, opened. It was a technical achievement

that took 17 years to finish and unites northern and southern

Europe by allowing passage via high speed trains through some

of the most forbidding mountains in the world. What shouldn't

be forgotten in this success, however, is that another rail

tunnel, also the longest in the world at the time, was dug though

these same mountains almost a century and a half earlier. It

was an achievement that changed the face of commerce and travel

across 19th century Europe and a Wonder of the Age of Steam.

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

| -Engineer

credited with designing the route: Robert Gerwig. |

| -Length

of the main tunnel: 9.3 miles (15km) - Longest in the

world at the time. |

| -Chief

Engineer of main tunnel: Louis Favre |

| -Number

of spiral approach tunnels: Five. |

| -Dates

of construction of main tunnel: 1872 to 1881. |

| -Number

of deaths during construction (estimated):177. |

| -Opening

date of the Gotthard Railway: May 22nd of 1882

|

The

Alps Mountains, running through the heart of Europe, had for

centuries been a barrier to easy travel from the northern side

of the continent to the southern regions. With the invention

of the steam locomotive in the early part of the 19th century,

railways quickly spread over much of Europe, but a short and

efficient connection through this section of the Alps was missing.

In 1850,

the Swiss government hired two of the most respected engineers

in the world, Robert Stephenson (whose father had invented the

steam locomotive) and H. Swinburne, to advise them on the best

method of making a railway connection through the Alps. The

pair proposed a route through the eastern Alps that would have

run from Lake Constantine to Ticino and then onto Milan. Rather

than a simple railway connection, however, the plan called for

a short, tunnel, high in the mountains, that would be reached

by a special, steep incline railway that used a cable or cog

system. This would have necessitated the transfer people and

goods several times between different types of trains to get

them over the mountains, making the route very inefficient.

Originally,

this course was supported by Alfred Escher, an influential Swiss

businessman in the area of banking and railroads. Escher had

been instrumental in pushing Switzerland to expand its rail

routes in late 1849 when he feared that rail development in

Europe would bypass his tiny Alpine country.

|

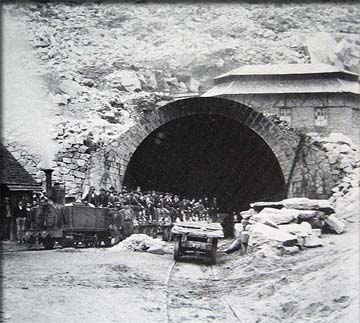

A

crew comes out of one of the tunnels riding a work train

in 1875.

|

The

eastern Alp line was never built and eventually Escher decided

that the Gotthard route was more promising. He threw all his

influence behind the project and by 1869 a decision was made

to start construction on the Gotthard railway. The next year

Escher helped found the Gotthard Railway Company which would

build and operate the line. The project, however, proved to

be an engineering challenge of the highest caliber.

The

Gotthard Pass

The

Saint-Gotthard Massif was the mountain range through which the

railroad would have to thread itself. With peaks as high as

10,500 feet (3,192 m), the best way through the range was the

Gotthard Pass. This pass through the mountains had been known

since ancient times, but was little used because of the difficulty

of crossing the turbulent Reuss River which intersected the

path. Crossing the Reuss was especially hard in the early summer

when it was swollen with snowmelt. With the construction of

a wooden bridge in around 1220, however, the trail was opened

for use with horses and pack mules.

With

a height of 6,909 feet (2,106 m), this original trail was too

difficult a climb for a normal railroad. It wasn't the height

so much, but the steepness of the path leading to the pass.

Normal railroad trains can only climb about 2 feet for every

100 feet of distance they travel. If a train tries to climb

a slope steeper than that, its wheels slip. Specialty railroads

can get around this by using cables or a cog gear that hold

the cars to a special part of the track, but this wasn't a solution

that would allow normal trains to travel the Gotthard pass.

Clever

Spiral Tunnels

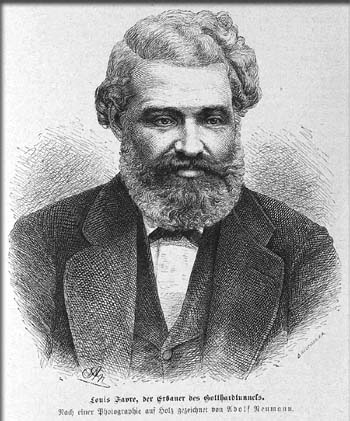

|

Louis

Favre

|

German

Engineer Robert Gerwig was charged with coming up with a route

through the mountains that would solve this problem. Gerwig's

solution required a 9.3 mile (15km) tunnel under the pass itself

along with five additional spiral tunnels on the approach to

the pass. These clever spiral tunnels would allow the trains

to gain height slowly by increasing the distance the train would

travel. The tracks would dive into a tunnel, then slowly climb

upwards on a large curve until the tracks emerged from the rock

at a higher altitude, but roughly the same location. This ingenious

arrangement allowed the train to gain height, while not making

the track itself too steep.

These

spiral tunnels, while shrewd engineering, were not unique to

the Gotthard line and had been used on the Brenner railway in

1867. The most difficult part of the project, instead, was the

long tunnel under the pass. A tunnel this long had never been

built before and would require a chief engineer of rare talent.

The man for the task turned out to be Swiss engineer, Louis

Favre.

Louis

Favre

Favre

was born in 1826, the son of a carpenter in a small village

just outside Geneva. He was not a well-schooled man, but acquired

his trade by observation and took night classes to learn whatever

else he needed.

On August

7th, 1872, Favre and his company won the contract to build the

main tunnel by underbidding 6 other companies. He promised it

would take only eight years and 56 million Swiss francs to complete

the job: one year and 12.5 million francs less than the next

lowest bid by his competition. This turned out to be a serious

miscalculation by Favre. While he would successfully complete

the tunnel and it would be considered his crowning achievement,

it would also lead to his financial ruin and ultimately his

death.

On September

18th, 1872, construction of the main tunnel commenced. Two crews

bored into the rock from each side, expecting to meet somewhere

about 4½ miles under the mountain. When they finally did, the

two tunnels they built were only 13 inches (33 cm) off from

each other horizontally and two inches off (5 cm) vertically.

For the 19th century, it was an amazing feat of engineering

by Favre and his crew.

|

Inside the

tunnel today. (Photo by Kecko. Licensed

under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

|

On earlier

projects, black powder had been used as an explosive to excavate

such tunnels. Later nitroglycerin (sometimes called "blasting

oil") was employed. While nitro was more powerful than black

powder, making the work go faster, it also was very unstable

and difficult to handle. Dropping it could initiate a blast

at the wrong time, killing dozens of workers. The Gotthard project

was the first tunnel to use the newly-invented product dynamite

instead. Dynamite had the power of nitro but was in a solid

form that included substances that made it less prone to be

set off by a shock, making the work of excavating with explosives

much safer.

Even

with using the newly-invented dynamite, however, the job was

a herculean effort, slowed by both technical and geological

glitches. On several occasions, large amounts of water broke

into the tunnel, causing the roof to collapse on the construction

crews. It is estimated that a total of 177 people were killed

before the completion of the project.

It is

little wonder that between low wages and high danger, Favre

found himself faced with discontent from his employees. During

1875, a strike by Italian tunnel workers was brutally suppressed

by the Swiss Army. Four people died and 13 other were wounded

in the incident.

Legal

disputes with his lender bank and the construction subdivision

of the Gotthard Railway Company further delayed the effort.

Eventually the tunnel was completed 10 months late. This was

a financial disaster for Favre as the contract he had agreed

upon fined him 5,000 francs for each day he went over schedule

for the first 6 months and 10,000 francs for each day after

that. Favre's company was driven into bankruptcy. Even worse,

however, Favre himself died four months prior to the completion

of the excavation.

Favre's

Death

On July

19, 1879, Favre and two others took an inspection tour of the

tunnel. Chief engineer in charge of that section of the tunnnel,

M. E. Stockalper, was with him, along with a visiting French

engineer. Stockalper had observed over the past few months that

the pressure of running the difficult and financially-failing

project seemed to be making Favre age prematurely and was concerned

about him. As an account of that day written by general secretary

of the company, Maxime Helene explained:

|

Favre's

body is carried from the tunnel.

|

"Up

to the end of the inspection he had complained of nothing, but,

according to his habit, went along examining the timbers, stopping

at different points to give instructions, and making now and

then a sally at his friend, who was unused to the smell of dynamite.

In returning he began to complain of internal pains. "My dear

Stockalper," said he, "take my lamp, I will join you." At the

end of ten minutes not seeing him return, M. Stockalper exclaimed,

"Well! M. Favre, are you coming?" No answer. The visitor and

engineer retraced their steps, and when they reached Favre he

was leaning against the rocks with his head resting upon his

breast. His heart had already ceased to beat. A train loaded

with excavated rock was passing and on this was laid the already

stiff body of him who had struggled up to his last breath to

execute a work all science and labor."

The

railway itself opened on May 22nd of 1882 and it the way changed

travel was done in Europe. Before the line initiated operations,

it is estimated an average of 80,000 people and 40,000 tons

of material passed through the Gotthard pass per year using

an old road. In the years following the opening of the railroad,

those figures jumped to 250,000 people and 300,000 tons. By

1908, the figures had further increased to 750,000 passengers

and 900,000 tons of goods.

So Favre's

tunnel and the railway it supported went on to be an unqualified

success.

On February

29th of 1880, when a small opening was made between the two

tunnel excavations working north and south to meet under the

mountain, a tin canister was pushed through the tiny gap first.

The canister bore the image of Favre, so that despite his death,

he came to be the first person to pass through the tunnel. Written

in French on the back of the can were the words: "Who else would

deserve to be first to go through? He was our champion, friend

and father. Long live the Gotthard!"

|

A

map of part of the route, showing two of the spiral tunnels.

|

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2016. All Rights Reserved.