pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Science of Archaeology

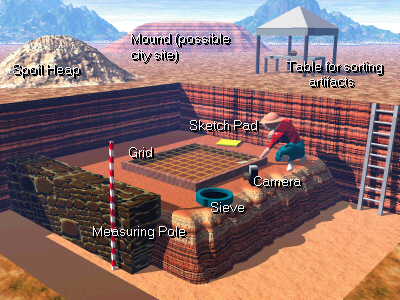

The word Archaeology means "The study of everything ancient." It is the science that looks into man's past to determine how our ancestors lived and why they did what they did. Though man has always had an interest in what previous generations were doing (the Egyptians took the trouble to record inscriptions off of tombs that were already centuries old) it is only in the last few hundred years that scientific archaeology has developed. During much of the 18th and 19th centurys' archaeology consisted of not much more than digging into promising sites hoping to find buried treasure or valuable artwork for museums. Dr. Heinrich Schliemann was one example of this type of archaeologist. Though Schliemann brilliantly deduced the location of the ancient city of Troy based on descriptions from the ancient poem The Iliad, he failed to excavate it properly and set off on a treasure hunt that ironically destroyed much of the remains of the city that he found so interesting. Archaeologists today are interested in much more thatnjust treasure. They want to examine a site and determine what the day-to-day lives of the ancient people were like. For this reason, archaeologists often find that the garbage pits, which show the remains of objects used in everyday life, are often the most interesting part of an excavation. Where to DigMuch of Archaeology is done though excavations. Scientists find a likely site, then dig down in the soil looking for ancient objects that are buried there. Sometimes the objects wind up in the ground because they were thrown away (as in the case of a broken pot), accidentally dropped (as with a coin) or purposely buried (as in a tomb). Tombs have always been excellent places for archaeologists to learn about a people. Buried bodies can be examined and often give important clues to the health of the former owners (Mummies have shown that the ancient Egyptians had problems with worms, arthritis and lung problems from sand and smokey fires). Also, the customs of some societies dictated that the person be buried with personal items, household effects, treasures and sometimes even servents. These remains can be studied to learn about the culture of that group. Unfortunately many tombs were robbed in ancient or recent history, depriving scientists of the valuable information they contained. In a few cases however, like the tomb of King Tut in Egypt and the Lords of Siapan in Peru, the graves have been excavated mostly intact. Scientists have a number of different methods to determine a likely place to start an excavation. If an archaeologist is studying the recent past, like the 19th century, he may find many of the buildings used at that time (perhaps an old factory or house) still standing. Even some buildings thousands of years old can still be visible if they were built well with stone, like Egypt's Great Pyramid. Even if no walls are standing, an ancient city or temple can often be identified by looking for a low, regularly-shaped hill (This is how Schliemann located the city of Troy). Low, regularly-shaped hills or mounds of earth can indicate a place where people have lived for a long time, perhaps a city. As parts of the city are torn down and rebuilt over time, the old rubble is often used as fill or foundation for new structures. Over hundreds and hundred of years this can create a layer effect. As scientists dig down through the mound, they see various layers for each rebuilding of the city. If a city is around for a thousand or more years, a dozen layers may have built up, with each layer representing a different period from the history of the city. Sometimes even when the remains of an old city can't be seen from the ground, it can be seen clearly from the air. Slight depressions in the soil over an old ditch or a bank over an old wall maybe seen from an airplane in the early morning or evening when shadows are long. Crop marks can also give clues to buried features. Plants will grow shorter and more yellow over buried walls and taller and greener over old ditches and pits. As the world has gone more high-tech, so have the methods scientists use to find old buried ruins. Infrared photographs taken from a plane can detect temperature differences on the surface of the ground due to buried features. It is possible also to detect underground features by using probes to measure the electrical resistance of the soil or changes in the Earth's magnetic field. Sometimes finding a site depends not on observations made at the site at all, but by carefully studying old records and documents, or tracing down legends. Running an ExcavationOnce a site is chosen for a dig, the excavation must be carefully planned and executed in order to get valid scientific results. The lead Archaeologist on a dig must examine the location and draw up a plan that specifies the areas he wants to dig up, and the amount of equipment and people he will need to conduct the work. Permission must also be obtained from the landowners and governments involved. The lead archaeologist might decide to dig a wide, shallow pit if the location was used recently for a short time since it is unlikely any artifacts would be deeply buried. On the other hand, he might decide on a deep, narrow trench if the site may have been used for hundreds of years and many layers have been built up. The most important aspect of a scientific excavation is record keeping. For that reason the site is divided into a grid of squares sometimes using stakes and string. As the scientists dig into the soil and unearth objects, each is cataloged with the location where it was found by using the grid number and how deep it was found. The object is also photographed and cleaned. A drawing is made showing precisely where within the square of the grid the object was located. This information will allow scientists to later piece together what the object may have been used for and why it was buried in that position. In general, the farther underground an object is found, the longer it has been buried. At a site that has been occupied for a long time, the lower layers represent earlier periods. By knowing what layer an object was found in, an archaeologist can estimate its age. Often this is done by figuring out what other objects are found in the same layer. It is easy to put a date on things like coins, pottery and charcoal. This helps give a time to other objects found in that same layer. Record keeping is very important to this process since it imperative to know what items were found together on the same level. Digging at an archaeological site is done slowly and is hard work. Much of the work is done with trowels, or even spoons. When objects are found, small brushes are used to clean off the remaining dirt without damaging the artifact. Nothing, no matter how small, is missed. Even the dirt is carried to a place where it is sifted to find little items the diggers may have missed with their eyes. After being completely checked, the dirt is put into a pile known as the "spoil heap." One of the most common items found at an ancient excavation is pottery. Since pots break easily, are cheap to make and hard to repair, they are often thrown out. Fortunately for scientists, even though pottery breaks under very little pressure, it does not decay when buried. This means an archaeologist can count on finding thousands of pieces of pots at any site that has been used for a length of time. A people's pottery tells a lot about them. For example, the level of their technology. Did they use a pottery wheel to make the pots or a mold? Were the pots fired in a low or high temperature kiln? The style of the pottery and decorations can tell scientists about the culture of the people. Was the pot made locally or did it come from some distant land via a trade route? Was the pot simple and cheaply made or elaborate and expensive? The color of the pot and the minerals in the material can give scientists a clue to where the clay it was made from came. Since different peoples used different styles of pottery it is also possible to trace the movement of that people across regions by the pottery they left behind. Getting the DateIt is important for scientists to be able to determine when an artifact was made. There are a number of techniques to do this, the most obvious being written records. In places like Egypt where many records were carved into stone monuments, it is possible for researchers to put together very accurate chronology based on this information. The Egyptians were great astronomers and records they made of the movement of the stars have been used to pinpoint dates in Egyptian history. What about places where there are no written records? In some cases it is possible to figure out dates by looking at pottery that was brought in from a neighboring land where there were written records. Since pottery styles will change over time, the pots can be traced to estimated dates. There are also scientific tests that can determine the age of some objects. Organic matter (material that was once living) can be dated to when it died by the amount of carbon-14 within it. The radiocarbon test detects more carbon-14 in more recent objects, and less in older objects. Measuring the amount of fluorine and other material in bones can give the relative ages of the bones, though it does not give a fixed calender date. The test can be useful for comparing the ages of two bones and was responsible for detecting the infamous Piltdown Man hoax. Thermoluminescence tests can be used to date pottery by detecting radioactive materials in the object and measuring minute amounts of light given off by them. Ruins composed of clay can be dated through magnetic dating. Over time the Earth's magnetic north has been moving. When clay is baked, an imprint of the Earth's magnetic field is locked into it. As long as the clay has not been moved scientists can determine when it was baked by measuring the difference between the magnetic imprint in the clay and known past locations of the Earth's magnetic poles. One of the simplest ways of estimating the age of wooden objects is through their growth rings. If a tree is cut open, its growth rings become visible. For each year that has gone by, the tree's cross-section has another ring in it. Whether it had been a good year for the tree, or bad, it is visible in the rings. Narrow growth rings can mean a drought. By matching a pattern of growth rings in an object with trees that are still living in the area where the object was made, it is possible to come up with a very accurate date for the object. High-Tech ToolsAs more high-tech tools become available, an archaeologist's ability to discover old ruins and relics increase. Photo's taken from space were key to discovering the lost city of Ubar in Arabia. On the other end of the scale, microscopes can be used to identify pollen grains of different plants that lived in an area. This can be used to identify farm fields, or other changes in the foliage at a site over time. Using these techniques, scientists have put together a clear and quite chilling picture of the slow deforestation of Easter Island over the centuries even though there are no written records.

One of the most promising areas recently opened by technology is undersea archaeology. Exploring the ruins of sunken ships or submerged cities can be extremely expensive and dangerous, but the results can be remarkable. Because the location is underwater it may have laid undisturbed by looters and curiosity seekers through out many centuries. In some cases the cold water may have also helped preserve remains. In shallow water, around one hundred feet deep, divers wearing aqualungs can excavate a shipwreck much as they do on land. The area is divided into a grid to help with record of where each artifact is found. If any of the ship's hull remains, the divers may first dig around it. This will tell them if the wreck is stable. Sometimes nothing of the ship itself has survived, but only its cargo. Large amounts of muck can be moved off the bottom by use of an air lift. An air lift is a long large tube that works like a vacuum cleaner. Compressed air is fed into the nozzle and as it shoots up the tube a suction is created. For more delicate work divers wave their hands or use soft brushes to clear silt off of artifacts. Artifacts, like coins, after long periods in the water can become stuck together as heavy solid clumps known as concretions. Aboard ship the concretions can be broken up with hammers or chemicals. To lift large concretions and other heavy items to the surface, bags are attached to the objects and then filled with air from extra air tanks. The bags become balloons and lift the items to the surface. To operate at great depths archaeologists must use submarines, remote cameras and special diving suits that can withstand the high pressures of deep waters. It was these methods that allowed scientist Robert Ballard to discover the resting place of the ship Titanic in 1985 almost three-quarters of a century after it had been sunk by an iceberg and sank in 1912. New and better techniques will continue to help archaeologists, but the key to understanding mankind is not with the technology alone, but through the dedication and hard work of archaeologists around the world. Copyright Lee Krystek 1999. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|