pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Incredible Automobile Race of 1907

In 1907 eleven men set out to take the newly-born automobile on an adventure across two continents and over deserts and through swamps. Would it be up to the challenge? In a article in the French newspaper Le Martin in January of 1907, the editors raised a challenge to the world: ...We ask this question of car manufacturese in France and abroad: Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Paris to Peking by automobile? Whoever he is, this tough and daring man, whose gallant car will have a dozen nations watching its progress, he will certainly deserve to have his name spoken as a byword in the four quarters of the earth... Not only did one man take on this impossible challenge, eleven men did. It became not only a difficult course to drive, but a race. Probably the most incredible automobile race of all time. In 1907 the automobile had only been around for a little more than twenty years. The vehicles were under-powered and unreliable compared to modern standards. Many people thought these temperamental machines would never replace the horse. Still, there was an enthusiasm about this new invention that is difficult for us to grasp today. If they could be driven the 10,000 miles from the capital of France to the capital of China, perhaps they were more than mere toys for the rich. The Motorists The contestants consisted of eleven men driving five cars: Charles Godard and Jean du Taillis (a correspondent for the Le Matin) would drive a 15-horsepower (HP) Dutch Spyker. A pair of French auto dealers sponsored matching 10HP De Dion Boutons. Another Frenchman named Auguste Pons would try his luck with a tiny three-wheeled 6HP Contal. The final, and most powerful car, was a 40HP Itala driven by Prince Scipio Borghese. Borghese was an Italian aristocrat, but his family had lost much of its money and he had opted for a career in the army. By age 36 Borghese had learned to be a consummate planner and had traveled extensively before the Le Matin challenge appeared. Driving with him would be two more Italians: Ettore Guizzardi, Borghese's mechanic, and Luigu Barzini, a journalist. It was decided that to avoid the monsoon rains, the race would be reversed and start in Peking in May with the cars driving westward to Paris. The course would take the contestants over numerous mountain ranges and two major deserts. In many cases there would be no real roads, but forest paths and caravan trails.

Prince Borghese used all his planning skills to give his team the best chance of winning the race. He arranged for extra fuel and spare parts to be cached along the route. Before the race started, he took a three-hundred mile ride on horseback to the mountain passes north of Peking carrying a bamboo pole cut to the width of his car to see if the Itala could squeeze through the tight trails. Where the way was too narrow, Borghese found an alternate route or hired troops of coolies to widen the path. Godard, driving the Spyker, was perhaps the exact opposite of the Prince. A bit of a con-man, Godard did a minimal amount of planning and sold most of his spare parts to purchase his first-class passage to Peking. He would be dead-broke when he arrived. His partner on the trip protested his lack of foresight, but Godard replied. "Either I shall never see Paris again or I shall come back to it in my Spyker, hot from Peking!" The start of the race was set for June 10th. The only problem was that the Chinese government, after first authorizing the race, refused to provide the racers with papers to travel through Mongolia. As the race day approached, both Godard and Borghese decided to start on time, papers or not, and risk the ire of the government. After they declared their intentions, the rest of the group decided to join them. They're Off! A French military band led the cars out of the city on the appointed day as the crowds around them cheered and celebrated with firecrackers. It wasn't long before the group began to have problems, though. A hard rain soaked the crews in the open cars and turned the road muddy.

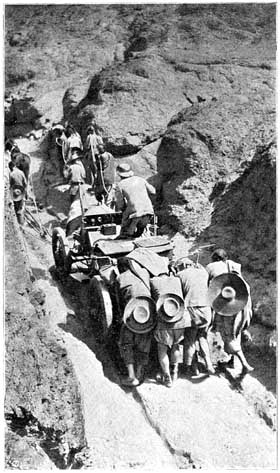

Soon they approached the Western mountains that separated northern China from the Mongolian plains. The paths were narrow. In some places the trail was cut out of a cliff with a shear drop into a gorge only inches from the car's tires. Much of the road was too steep for the car's little engines, and mules or men pulling ropes hitched to the cars were needed to drag them through the mountain passes. Once the Itala got away on a downhill slope with Guizzardi at the wheel. The brakes could not hold the vehicle on the steep grade. The mechanic spun the wheel wildly, trying to keep the car from driving off the narrow road into the gorge beside the trail. By some miracle he brought the Itala to a stop at the bottom safely. Gobi Desert After the mountains the next obstacle for the racers was the forbidding Gobi Desert. Pons quickly ran out of gas and he and his co-driver found themselves stranded. They began walking back to civilization, but they had almost no water. Fortunately nomadic Mongolians found the pair before the heat killed them. Pons, having narrowly escaped with his life, decided to give up the race, leaving only the four remaining teams to trek across the hot, sandy wastes. His little three-wheeled car was left to rust in the desert. The racers kept on track through the desert by following the telegraph line. The engines on their cars were not built with such intense heat in mind and quickly started boiling over. This meant the teams were forced to feed the radiators their own reserves of drinking water to keep them running. A dangerous practice. Barzini used the telegraph to report back to his newspaper as often as he could. At the tiny village of Hong-Pong, Barzini strode into the telegraph office to send that day's report. He noticed that his telegram was marked as "No. 1" At first Barzini thought that meant it was the first telegraph sent that day. He was amazed to find out it meant that his was the first telegraph to originate from Hong-Pong in the six years the station had been there. Travel in the desert, as it turned out, was faster than the mountains. It had taken five days to get over the mountains, much slower than a camel caravan. The Itala only took four days to cross the desert, however, something that a caravan did in seventeen days. As the race left the Mongolian plain to enter the mountains at the Russian border, Prince Borghese's team (in the Itala) was in the lead at least a half-day in front of the competition. The Wilderness of Siberia Borghese hoped that he would make good time traveling through Siberia. The maps showed a military road stretching across the wilderness. What the maps did not show was that the road had been abandoned when the Trans-Siberian Railway had been completed four years before. The forest had reclaimed much of the road and many bridges had been washed away. Others were in bad shape. Borghese took to running at them at full throttle trying to get across before they collapsed completely. The race nearly ended for the Itala when it tried to cross one bridge. Guizzardi was at the wheel and Borghese ordered him to drive slowing across the rickety structure. They'd gotten more than halfway when suddenly the planks under the Itala's rear wheels gave way. The back of the car plunged through the bridge as the vehicle did a backwards somersault. Barzini, the reporter, fell the farthest. He found himself under the bridge with a rain of broken planks and debris falling on him. Borghese found himself hanging under the car covered with oil. Guizzardi, who was thrown from his seat in the fall, managed to extract the Prince and the reporter from the wreckage. It was a miracle that all three survived without major injury.

The Itala was in good shape, also. A heavy beam had slowed the fall of the front of the car and spare tires had cushioned the impact of the rear. It took three hours to pull the car from the wreckage of the bridge and get it back on to the road, but when Guizzardi cranked the handle, the machine started right up. "She seems quite safe," he said with a smile. Occasionally the racers would use the railway tracks for a road. Two planks would be used to allow the car to mount the track with one set of wheels riding on the outside of the rails and one on the inside. At first the tracks seemed a great relief after fighting their way through waist-deep mud and ruts. After a while, though, the jarring and jerking of the auto along the sleepers became quite nerve-racking. The motorists called the movement a "horrible dance." Once the Itala got stuck on the tracks before an oncoming train. The crew worked furiously trying to get it loose with levers. They got it safely off just in time. They had been having trouble with the Itala's wheels all through Siberia. In order to cope with the mud, Prince Borghese had wrapped chains round the wheels to give them traction. This worked well but put stress on the wooden spokes making them crack. Temporary repairs were made but the problem continued to worsen. Finally the left-front wheel splintered into pieces leaving the Itala stuck, unable to move another foot. Fortunately the nearest village contained a cartwright of considerable skill. He managed to chop a new wheel for Borghese out of aged pinewood using only a hatchet. "The hatchet becomes in the hands of the Russian peasant a wonderfully exact tool," observed Barzini. In only a few hours after this major problem occurred it had been solved and the Itala was on its way again. The Final Lap

From that point on the trip became comparatively uneventful. Only one incident caused any problem for the Prince. A policeman in Belgium stopped the Itala for going over the speed limit. When the policeman asked for identification, the Prince announced, "I am Prince Borghese - we have just driven from Peking, China." There was a delay as the policeman confirmed this incredible tale. On August 10th, 1907, the Itala entered Paris winning the race. It had taken sixty-one days to drive from Peking to Paris. Crowds cheered and lined the streets into the city. "It all seems absurd and impossible; I cannot convince myself that we have come to the end, that we have really arrived," wrote Barzini. The pair of De Dion-Burtons and the Spyker arrived in Paris 20 days later. Godard, who had been removed as the driver in Berlin over a money dispute with Le Martin, never completed the trip and a driver from Spyker had to steer the car into Paris. Prince Borghese and the other drivers had proved that the car was here to stay. Others have attempted to trace Prince Borghese's trail, but with limited success. In 1957 Luigi Barzini Jr. asked clearance from the Russians to retrace his father's route, but they would not give him permission. In 1997 a road rally was held to commemorate the race, but the route did not pass through Siberia. So 1907 race has never quite been repeated. The racers' feat stands alone as one of the most sensational achievements, unequaled, in automobile history. The race route from Peking, China, to Paris, France.

A Partial Bibliography Peking to Paris: Prince Borghese's Journey Across Two Continents in 1907, by Luigu Barzini, Translation by L.P. DE Castelvecchio, Library Press, 1973. Prince Borghese's Trail, by Genevieve Obert, Council Oak Books, 1999. Copyright 2003, Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|