pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

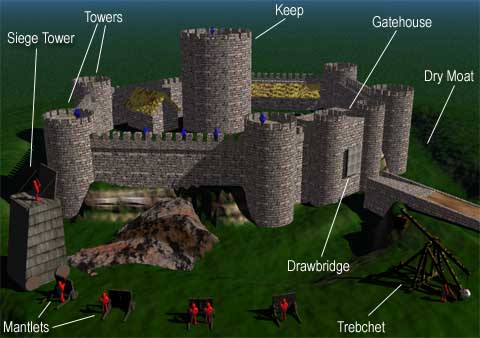

Castles Castles are often thought of as Romantic symbols of a past age. Their turrets and walls bring to mind kings and queens of royal blood. Their drawbridges and gates make us think of knights in shining armor and handsomely dressed visiting nobles. They were certainly a major feature of medieval life. Over the centuries some 10,000 castles were built in Germany, 10,000 in France and another 2,000 in Britain and Ireland. Do we ever stop, however, to consider what function a castle really had? Those towers and walls just weren't just for show. The castle was the home of a Lord, the business offices of his territory, and most importantly the base of his military power. The castle was a machine of war. History The word castle comes from the Latin castrum, which means "a fortified military camp." By the Middle Ages, however, castle came to mean a stronghold which was also the residence of a lord. In some cases the castle might be an elaborate palace, in others merely a manor house with a wall. The earliest castles, build in the 6th and 7th centuries were simple affairs mostly made out of wood. A ditch was dug in a circle and the dirt piled up in the center to make a hill. On the inside of the ditch a wooden fence was erected and a tower built on top of the man-made mound. Such a castle could not fend off a sustained attack, but it might encourage raiders, often Vikings, to skip this particular manor and assault the next. The ditch eventually became the "moat" and the mound became known as the "motte." Castle designers soon learned to use the natural terrain to make their castles more secure. A river could be diverted into the ditch to make it a water obstacle. Mottes could be made higher if they were placed on a natural hill. Being on a high ground gave the castle defenders a major advantage: they could see trouble coming at a distance and attackers were forced to climb uphill slowing their assault and making them easier targets for the defender's weapons. Over time castles became more and more elaborate and took on the job of not just protecting he Lord and his immediate family, but of the whole manor or town associated with it. They became more permanent and were built out of long lasting stone rather than wood. Castle Construction A typical castle would have these components: The Keep - The keep was a large central tower that served as the residence of whatever Lord owned the castle. It usually contained a great hall for entertaining guests on one level and quarters for the Lord family on a higher level. The keep had thick walls and heavy doors so that it could be used as last holdout for the Lord should the outer walls be breached. Keeps often also contained secret passages that might allow a Lord to slip out of the building without his enemies being aware that he had departed. Sometimes the door of the keep was located on the second floor and was reached by means of a exterior wooden stairway. To block invaders in time of war the stair could be burned. Courtyard - Sometimes the courtyard was referred to as the "bailey" though that term was often applied to the outside walls as well. Inside the courtyard were a number of buildings that were either freestanding or built into the walls. Almost all courtyards had a well to provide fresh water for the castle. Without a source of fresh water, for drinking and fighting fires, castle defenders could only hold out a few days when under attack. Chapel - Since the castle was the home of a Lord, he usually provided for a chapel inside the walls. A rich Lord might have his own resident priest, while others would have to be satisfied with waiting for the traveling priest to make his rounds. Curtain Wall - The curtain wall surrounded the castle and could be as thick as six feet at the base. On the interior near the top of the wall ran a "Allure," or walk, from which it was possible to look over the wall at various openings to see the countryside . From here archers could fire down upon enemies below. The top of the walls, known as the battlements, were often "crenelated" with a series of openings in a tooth-like pattern. The defenders could string their arrows in safety behind the wall, then step out into the opening to fire. Where there were no openings in the wall castle walls designers provided slots, or "loops" through which arrows might be fired.

A large castle might have several sets of concentric walls so that if one fell, the inter portions of the castle might still be secure. In between the walls were additional courtyards and buildings of lesser importance. Towers - In addition to the keep the castle would typically have a series of towers embedded in the walls, especially were two sections of outer wall joined at an angle. With additional height, these towers could provide a better view than could be gotten at the top of the wall. Towers also usually jutted out from the wall allowing archers on top or inside the tower a good angle to fire from so they could protect the base of the wall. Towers were square originally in shape, but this made them subject to "mining." Enemy soldiers would sneak up to the corner and attack the tower, or the underlying soil, with picks and shovels. Firing arrows at anyone standing at the bottom corner of the tower proved to be difficult so castle designers eliminated the problem by making the towers round or with a "D" shape that they had no exterior corners. Inside the towers was typically a spiral staircase. The clockwise direction of the spiral was designed to allow a defender to use his sword hand effectively while backing up the staircase. Access to the wall-walk was often limited to only these tower stairways. This was also a defensive measure. Should invaders make it over the top of the wall onto the walk, the doors of the towers could be closed and barred leaving the intruders stranded on the wall and exposed to arrows coming from the top of the towers or the courtyard below. Gatehouse - Perhaps the second-largest single structure in the castle was the gatehouse. Since it was the most vulnerable to attack, castle designers gave it multiple defense mechanisms. The most obvious of these was the drawbridge. The drawbridge spanned the moat providing access to the castle and was hinged at the base so that it could be drawn up in time of war.

Within the gatehouse was a passage that led to the courtyard. A large grill, or portcullis, could be lowered from above to block the passage. The best designed gatehouses had one portcullis at each end of the passage. These could be dropped into position to trap unwanted visitors. From loops and "murder holes" in the ceiling castle defenders could fire arrows and drop boiling water onto anybody in the passageway. A gatehouse might even have a trap door in the passage floor. When released those trapped in the passage would tumble into a pit below the gatehouse. The floor of the pit was often lined with sharpened spikes. Siegecraft With all these defenses you might think that a castle was impregnable, but it wasn't. Sometimes attackers would try and take a castle quickly by storming it before it could be closed up, but the usual way of attacking a castle was to lay siege to it. This involved surrounding the castle so that no people, food or water could get in and out. The attackers could then just wait until the castle's food or water supply ran out and it had to surrender. Unfortunately this could take weeks or even months if the castle had been well stocked and it had it's own water supply. To speed up a surrender attackers employed a number of techniques: The Trebchet - This weapon was a giant sling powered by a counterweight. It was capable of throwing hundreds of pounds into, or even over, the castle walls. The projectile was often a boulder, but sometimes other objects were used. A dead, rotting cow might be thrown inside the walls to spread disease. Decapitated human heads might do the same thing and also demoralize the defenders. In the 12th century, during the siege of Newbury castle, the King threatened to kill the lord of the castle's son if the lord did not surrender. When the Lord, John Marshal, replied that he could have other sons, plans were made to deliver the son to his father by sending him over the wall using a Trebchet. The king relented, however, and the plan was never carried out. The Mangonel - This was a smaller version of the Trebchet that used the torsion principal instead of a counterweight. It would usually be used to throw small missiles. The Mantlet - A portable wooden wall that could be rolled forward to protect troops from attack by archers on the castle walls. The Ram - The ram was a tree trunk stripped of branches and often capped with an iron point. It was then hung by chains from a rolling shed. The shed (often called a "mouse") was covered with wet animal skins to protect it from flaming arrows. The mouse's walls sheltered the soldiers while they worked the ram. The mouse was dragged up to the front door of the castle and a crew of men would swing the ram back and forth hitting it against the entrance. Eventually the door would give way. The Ladder - The attacking army could use ladders to attempt to climb the walls, but this was a dangerous practice. A soldier climbing a ladder was totally unprotected from archers in the towers and on the walls and it was unlikely he would make it to the top unless they were distracted. A forked stick could also be used by defenders to push the ladder away from the wall with unpleasant results for anyone hanging on near the top.

The Siege Tower - This rolling tower (sometimes referred to as a belfry) was taller than the curtain walls and was pushed up to the castle so a bridge was lowered across to the top to the wall. Attackers could then rush up the tower, across the bridge and into the castle. Like the ram, the tower was covered with wet skins to protect it from flaming arrows. Neither the Ram nor the Siege Tower could be used, however, until the moat was filled in creating an even surface right up to the walls. To do this the attackers had to build a long shed covered with wet skins all the way up to the moat. Using this they could carry rocks, dirt, brushwood and other material right up to the castle so they could be thrown into the moat until it was level with the ground. Then, on top of this, a wooden boardwalk would be built so the siege machines could be rolled across a smooth, level surface. Mining - Another approach was to dig a tunnel under a wall of the castle and prop up the roof up with wooden beams. When enough of the wall had been undermined, the beams were set on fire. They would burn through and the wall would collapse. To counter this kind of attack defenders would dig their own tunnel and undermine the attacker's tunnel. Occasionally the tunnels would meet and an underground battle might ensue. The End of the Castle Period As better siege weapons were invented, castle designers countered with changes in castles meant to thwart them. In the end, however, the invention gun powder and artillery limited the effectiveness of the castle as a war machine. Cannon balls could be used to batter down the thickest walls and rockets and bombs could fly over them. By the 15th century castles were being built less for their military effectiveness and more for show. Perhaps this trend reached it's apex with the construction of Neuschwanstein built in the German Alps near Fussen, Bavaria in 1886. Neuschwanstein, despite numerous towers and walls, was built purely a spectacular looking palace with no attempt at defense. Perched on a peak amid the mountains it was a beautiful work of architecture. So much so, that Walt Disney used it for his inspiration for Cinderella's castle in Disneyland.

A Partial Bibliography Castles and Fortresses by Robin S. Oggins, MetroBooks, 1995. The Medieval Fortress by J.E. Kaufmann & H.W. Kaufmann, Combined Publishing, 2001. Copyright Lee Krystek 2003. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|