pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Those Fabulous and Foolhardy Flyers I

Part 1: Flight from Icarus to Orville In Greek myth the great inventor Daedalus and his son, Icarus, escaped from imprisonment on the island of Crete by making wings of feathers held together with wax. The flight was successful until Icarus, ignoring his father's warning, flew too high and too close to the sun. The wax holding together his wings melted and he fell into the sea where he drowned. Thus one of man's earliest tales about an attempt to conquer the sky ended in tragedy: A warning about the foolishness of trying to ascend to the realm of the gods. But while this cautionary tale was being told by wandering poets in the courts in Greece, on the other side of the world the Chinese were experimenting with the first kites. Devices thast would later be key in helping man to learn how to eventually become a master of the sky... Man's fascination at watching birds take flight and his desire to join them started before Icarus and continued throughout history. According to legend, King Kay Kavus, who ruled Persia in 1500 BC, tried to fly by constructing a throne of wood and gold to which he attached eagles that had been specially trained to increase their strength. Above the heads of the eagles were dangled legs of mutton. As the hungry birds flapped their wings to reach the food, they carried the King's throne up into the sky. The "Birdmen" More serious attempts at flight came later. In 852 AD the Moor, Armen Firman, constructed a voluminous cloak with the intention of using the garment like wings to glide. Jumping from a tower in Cordoba, Spain, Firman survived with only minor injuries because his outfit caught enough air in its folds to break his fall. While trying to fly Firman had invented a primitive version of the parachute. Other "birdmen" were not so lucky. In 875 AD an Andalusian physician named Abbas ibn-Firnas "covered himself with feathers for the purpose," and according to one account, "attached a couple of wings to his body, and getting on an eminence, flung himself into the air." Witnesses said that ibn-Firna's glide was successful, but the landing was hard. "...not knowing that birds when they alight come down upon their tails, he forgot to provide himself with one." Ibn-Firnas severely injured his back.

The great Leonardo da Vinci, the genius of the Renaissance whose talents were spread over the fields of art, music, architecture, mathematics, engineering and science, became obsessed with the problem of flight. He spent the last forty years of his life filling notebooks with thoughts on aeronautics and over 500 sketches of flying machines, including plans for a primitive helicopter. Man began to make more progress toward flight in 1670 when Francesco Lana de Terzi, an Italian Jesuit, proposed one of the first lighter-than-air vehicles. Terzi had studied the science of atmospheric pressure and realized that a container with a vacuum inside could be lighter than the air it displaced causing it to rise from the ground much the way air rises as bubbles in water. Terzi then described a ship lifted by four globes from which the air had been pumped out. In theory, Terzi's idea might have worked, but the material he chose to make the globes from, thin copper foil, would have never withstood the pressure of the outside air. They would have collapsed before his ship would have made it an inch off the ground. Lighter-than-air A century later the brothers Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier applied the same principles to create the first hot air balloon. The Montgolfiers were papermakers from the French town of Annonay. Hot air expands, making it less dense than the surrounding cool air. The Montgolfiers had noticed that for this reason a paper bag filled with hot air would rise. During a public demonstation they were able to send a large paperlined linen balloon filled with hot air up to 6,000 feet and across the countryside for a mile. This was followed by the the first human lighter-than-air flight on November 21, 1783, when two volunteers rode a Montgolfier balloon for 25 minutes over Paris. As exciting as the discovery of lighter-than-air flight was, it didn't seem to offer the speed or maneuverability that man envied so much in birds. So work on heavier-than-air flight continued, though in some ways the ideal of the bird was misleading. Most early aeronautical inventors designed their craft as a type of machine now known as a ornithoper. An ornithoper is a device designed to fly by flapping its wings like a bird. Flying machines, when they did come, used a simpler and more efficient way of producing the forward velocity needed for flight: the air-screw or as it later became known, the propeller. Early designers were hampered by the lack of a way to power their machines. Most plans depended on human muscle to provide the energy to flap the mechanical wings. However, in the 17th century, Robert Hooke, a distinguished mathematician, physicist and inventor, calculated that man did not possess the physical strength to power artificial wings (indeed a third of a bird's body weight may be his flying muscles). That meant some additional, external source of power would be needed. Hooke's thinking was correct for his time, though in 1977, through the use of modern technology, the first human-powered flight finally did occur when a lightweight pedal-powered plane named the Gossamer Condor flew for a distance of slightly greater than a mile. Sir George Cayley perhaps did more than anyone else to set the stage for the first heavier-than-air flight. Cayley was born in 1773 in Yorkshire, England. Growing up in a wealthy family, Cayley was able to pursue his interest in science for most of his life. His first work in the area of flight was triggered by the Montgolfier's balloon. He carefully studied how birds flew and came to understand their aeronautics better than anyone else at that time. Cayley also came to realize that any successful flying machine would have to conquer the problems of lift, control and propulsion, issues that most other aeronautical inventors at the time did not seem to comprehend. Cayley's work reached a peak in 1853 when the 80-year-old inventor had his coachmen fly what must have been a primitive glider. The flight was successful, but the man jumped out of Cayley's device upon landing and declared, "Please, Sir George, I wish to give notice. I was hired to drive, not to fly!" The Aerial Transit Company

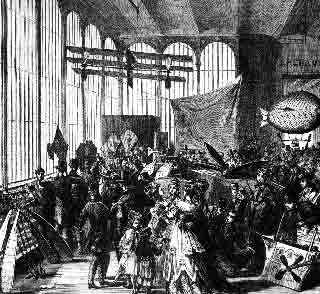

The fact that the flying machine had not been invented did not prevent the first airline from being incorporated. William Henson and John Stringfellow launched the Aerial Transit Company. Henson had come up with a design for an "Aerial Steam Carriage" in 1840 but didn't have enough capital to build it. By selling shares in the airline they hoped to raise the money they needed. Colorful pictures of the machine appeared in journals like The Illustrated London News, and L'Illustration, a French publication. Pictures of this nonexistent craft showing it plying the skies over exotic locations like China and Egypt also wound up on souvenir items. Finally the tremendous publicity caused a backlash and investors backed out. Henson appealed for help from Cayley, but Cayley was unwilling to give anything but moral support. Eventually the Aerial Transit Company crashed and went out of business. However, the images of the flying machine steaming across the skies stimulated the minds of many other would-be aeronautical inventors. It also stimulated Cayley's mind. Cayley knew that Henson's device as pictured would have at least two problems, First, a steam engine as they existed at the time would be too heavy to use on an airplane. Second, the large single set of wings necessary to give the Aerial Steam Carriage enough lift would be ripped apart by the stress flight would put upon them. Cayley realized that the way to solve this problem was to have two or three shorter wings placed one above the other with enough space between them to allow the free passage of air. This multiwing design was adopted by a number of later aviation inventors, including the Wright Brothers. In 1868 the fledgling British Aeronautical Society decided to sponsor an exhibition of flying machines at London's Crystal Palace. None of the machines on display had yet been able to carry a human being aloft in a powered, heavier-than-air flight, but the display seemed to capture the imagination of the public. Hanging high about the exhibition was a new version of the Aerial Steam Carriage redesigned by Stringfellow to have three stacked wings. The plane never flew, but as before excited many imaginations. Steam-Powered Machines In the 1890's Hiram Maxim, an American inventor who had resettled in Britain, became interested in flying machines. Hiram had already invented a 600 hundred round-per-minute machine gun in 1884 that had made him rich and famous. Then Maxim concentrated his efforts on the problem of powering a plane. "The motor is the chief thing to be considered," wrote Maxim in a 1892 issue of The Cosmopolitan. "Scientists have long said, 'Give us a motor and we will soon give you a successful flying machine.'" Maxim solved his motor problem by building an enormous biplane with two 180 horsepower steam engines each driving propellers 18-feet across. The craft was almost 200-feet long with a wingspan of 107 feet and weighed, with its 3-man crew, an incredible 8000 pounds. To test his invention Maxim built a special track. The track was designed much like that of a modern roller coaster. One set of rails supported the flying machine from underneath while a second set above prevented it from lifting more than a few inches off the track. With this system Maxim was able to run tests with the machine with no fear that it would get out of control and crash. Journalists that visited Maxim's test site reported that the huge biplane roaring down its track was an awesome sight. Once Maxim was in the cockpit and the propellers were up to speed he would yell, "Let go!" and then according to a reporter "A rope was pulled, the machine shot forward like a railway train, and, with the big wheels whirling, the steam hissing, and the waste pipes puffing and gurgling it flew over the eighteen hundred feet of track in much less time than it takes to tell it." Despite its power and speed Maxim's machine was uncontrollable. On its final test run an upper rail snapped and the giant machine flew free for a few seconds. Maxim cut the engines and the device crashed to the ground never to rise again. If nothing else Maxim's experiments showed that a powerful engine could lift a very heavy object. The final crash also demonstrated that any successful flying machine would require a means of controlling and guiding it in flight.

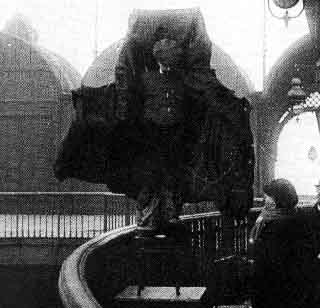

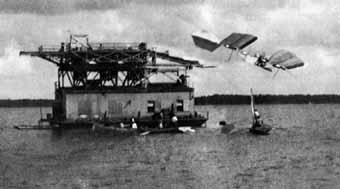

The first machine ever to leave the ground under its own power was built by Clement Adler. A distinguished electrical engineer, Adler got the flying bug and in 1882 he started construction of a flying machine. The result was a bat-like monoplane driven by an exceptionally-light steam engine. In a test on October 9th, 1890, Adler apparently was able to get the machine, which he had named "The Eole," to raise itself above the ground some eight inches for a distance of 165 feet. But like Maxim's, Adler's machine lacked control and was incapable of sustained flight. Later attempts by Adler to build a more sophisticated flying machine for the French military failed, though Adler later was to claim he'd made flights with it as high as 1,000 feet. Otto Lilienthal's Gliders Perhaps the man who knew the most about flight control as the 19th century entered its final decade was Otto Lilienthal. Lilienthal was a German engineer who had dreamed of building a flying machine since he was a boy. Lilienthal built a series of gliders that he tested from a hill he had constructed near his home. The gliders were similar to modern "hang gliders" and would be launched by Lilienthal carrying the device and running down from the summit of his hill, then jumping into the wind. With practice, Lilienthal learned to get his gliders to carry him more than 150 feet. Later, Lilienthal started testing his gliders at the higher Rhinowner Hill near Berlin. There he was able to achieve flights of over a 1,000 feet. While he was successful at building gliders, Lilienthal's attempts to build a flying machine failed. He built his two powered planes to use a flapping motion to provide forward movement, instead of an airscrew, and they never achieved flight. Before he could attempt a third design he crashed a glider and broke his back. He died the next day on August 10, 1896. However his work had inspired another man fascinated with manned flight: Octave Chanute. Chanute was born in Paris and immigrated to America as a child. He earned a degree and over the years became regarded as one of the United States most successful engineers. Chanute became interested in aviation after studying engineering problems surrounding the wind. In 1896 he teamed up with three other men with aviation interests, William Avery, William Butusov and Augustus Herring. In 1896 they went to a site on the south shore of Lake Michigan about 30 miles east of Chicago. There wind had blown sand into hills that rose up some 300 feet above the beach. They experimented there with several gliders. Lilienthal had kept his gliders under control by shifting his body to change the center of gravity of the craft. It was Chanute's belief that any successful plane would have to be naturally stable in all wind conditions without the need of physical gyrations of the pilot. One of the gliders the group tested had been designed by Chanute himself so that he could change the number of wings (up to twelve) and place them stacked at the front or rear of the craft. This glider, nicknamed "Katydid" because of its insect-like appearance, when configured with five wings in front and one in the rear produced the kind of stability Chanute was looking for. The party would return a number of weeks later with improved gliders that would convince Chanute that it was possible to built an inherently stable aircraft. Langley vs. the Brothers from Dayton As the new century dawned, men all over the world worked endless hours on their dreams hoping to be the first to succeed in building a powered flying machine. Two parties seemed to have pulled in front: One was a respected scientist from a well-known institution who was backed by the resources of the U.S. government. The other was two brothers from the Midwest who owned a bicycle shop. Samuel Langley was already a well-known astrophysicist when turned to the problem of flight. As the Assistant Secretary and later the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Langley had the staff and money to pursue the problem relentlessly. At first he built model rubber-band-powered gliders. These tests led him to believe that the major difficulty with constructing a flying machine would be to build an engine powerful and light enough to work in an aircraft. His staff labored over several years to build the machines Langley would launch from a catapult on top of a houseboat anchored in the Potomac River about 30 miles south of Washington near Quantico.

Langley's first few craft were total failures, but number six and seven, both unmanned gliders, each flew for over a minute. This convinced Langley that he was on the right path and in 1898 he persuaded the War Department to give him a grant of $50,000 and several years to develop a flying machine. About the same time as Langley was starting his work for the War Department, 32-year old Wilber Wright wrote a letter to the Smithsonian Institution requesting information on aeronautics. He and his younger brother Orville, sons of a United Brethren Church bishop, had always been mechanically inclined and had started a successful bicycle shop in 1896. The news of Otto Lilienthal's death triggered an interest within them to do some aeronautical research of their own. Their move to enter the race to build the first flying machine was as much a business decision as anything else. Wilber explained several years later that human flight was, "almost the only great problem which has not been pursued by a multitude of investigators, and therefore carried to the point where further progress is very difficult." The brothers plunged into research by reading every book in the Dayton area on the subject of flight. They were amazed to find that nobody had really figured out the problem of how to control an aircraft once it was in the air. By carefully studying buzzards in flight, however, they noticed that the animal kept its balance by a slight twisting of its wing tip. They built a kite that could warp it wings slightly and found it to be an effective method of control. Next, they built a glider capable of carrying a man using the same wing-warping technology. Kitty Hawk, a small village on a narrow barrier island off the coast of North Carolina, was selected as the brother's test site because of the constant wind, wide beach and lack of trees or bushes. Wilbur arrived there on September 13, 1900 to be joined by Orville a few days later. At first they tested the glider tied down like a kite. It was 17-feet across with two stacked wings and designed so that the pilot could lay face down on the lower wing. The wing warping was controlled by a bar at the pilot's feet, while a hand lever was used to control the craft's up and down motion by moving a wing-like surface (later to be called an elevator) that stuck out from the front of the glider. Later they took the craft to a large sand mound, called Kill Devil Hill, and did some manned glides that went as far as 400 feet.

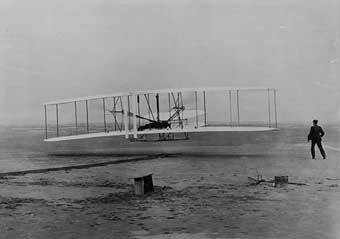

The next year they returned with a new, heavier glider and lumber to build a permanent shed. Octave Chanute, with whom the brothers had been corresponding to get advice, visited the camp and provided Wilber and Orville with two assistants. After some adjustments, the forward elevator seem to control the craft's up and down motion extremely well, but turning was a different matter. Returning to Dayton, the brothers began to suspect that there were errors in a set of tables that Otto Lilienthal had compiled on the lifting effect of air pressure on wing surfaces at various speeds and angles. To prove this they built a wind tunnel and tested wing shapes in it to get their own data. Armed with this new knowledge they returned to Kitty Hawk in 1902 with a new glider. Still, the problems with turning continued until Orville realized that the craft needed a movable tail, or rudder. With this change the glider soared across the dunes of Kitty Hawk under perfect control. The race to be the first to test a successful airplane was on. As they prepared to return to Kitty Hawk for the 1903 season, the brothers checked the newspapers carefully, following the progress of Samuel Langley, who appeared to be the only other person close to inventing a working flying machine. This time they would be taking with them to Kitty Hawk a glider/flying machine to be powered by a 12 h.p. gasoline engine they had designed and built in their own shop.. After they arrived at their beach camp the news came: Samuel Langley's latest attempt to test a flying machine on October 7th had failed. For the moment the brothers had the field to themselves, but perhaps not for long. On November 8th Langley was scheduled to make a formal request for more funds to continue his project. Despite bad weather and a broken propeller shaft they managed to get the new machine put together. With the engine the craft tipped the scales at over 600 pounds without a pilot. This meant that it could not be launched by having crewmen pull it along by its wingtips as was the case with earlier gliders, so the brothers built a wooden track. The flyer would roll along the track on a wheeled dolly that would be left behind when the plane took off. The craft would then land on a pair of skids.

On December 17, 1903, the brothers were ready to try a powered flight from level ground. An earlier test a few days before had led to a crashed flying machine and forced several days worth of repairs. With help from the nearby Lifesaving Station the brothers laid the takeoff track and positioned the aircraft. A coin was tossed to see who would be the pilot and Orville won. At 10:35 AM the engine was revved up and the restraining wire was released. The flyer, under its own power, picked up speed and was going about seven or eight miles an hour when it lifted off the track. It climbed to about ten feet, then settled gently to the ground. The flight was short, only a little over a hundred feet, but it was the first time a manned, heavier-than-air vehicle had gotten off the ground under its own power in controlled flight and landed at a spot as high as it had started from. The Wrights made three more flights that day going as far as 852 feet. Then a savage gust of wind caught the machine as it was parked near their campsite, picked it up and smashed it beyond immediate repair. The brothers were not disappointed, however. They had flown and, as they said in a telegram that day to their father, "the age of the flying machine had come at last." Continue with the story of early flight in Part 2: From Wilber to War Copyright 2001Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|