|

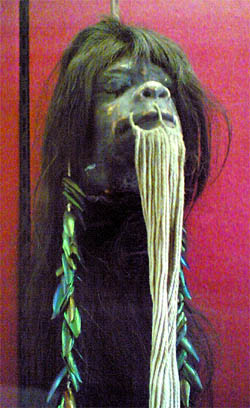

A

shrunken head in a musuem: fake or real? (Copyright

Lee Krystek, 2011)

|

The practice of head hunting - removing the head

of an adversary after killing him in battle as a trophy of the

victory - is historically widespread over much of the world.

In the 3rd century B.C. Chinese state of Qin, soldiers would

collect the heads of their fallen enemies and tie them around

their waist to terrorize and demoralize their opponents during

battle. In New Guinea, the Marind-anim tribe would take the

head of their enemies to control their spirits and would often

also cannibalize the flesh of their bodies. The Celts of Europe

also practiced headhunting up through the end of the Middle

Ages. A successful Celt warrior would nail the heads of his

enemies to his walls as a warning to others.

Despite the many forms of head hunting around

the world, only one group traditionally practiced the art of

taking a trophy human head and reducing it in size to that of

a man's fist. Head shrinking, as this practice has come to be

known, was the exclusive providence of the Jivaro Indians who

live in Ecuador and the nearby Peruvian Amazon. The Jivaro are

divided into smaller sub-groups which include the Shuar, Achuar,

Huambisa and the Aguaruna tribes.

The

Jivaro

When the Spanish conquered much of South America

starting in the 16th century, they found the Jivaro a difficult

problem. They were fierce warriors who were not easily subjugated.

According to records, in the year 1599 the tribes of the Jivaro

united in a revolt against the Spanish. Apparently 25,000 colonists

were killed during the attacks. During the uprising the Jivaro

raided the town of Logrono and took out their anger over a tax

on the gold trade by seizing the governor and pouring molten

gold down his throat.

|

A

tsantsa on display in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

The lower face and jaws jut outward as an artifact of

the shrinking process. (Credit Narayan

k28, licencsed through Creative

Commons Attribution

3.0 Unported)

|

After this rebellion the Jivaro territory, despite

its value as a gold-producing region, was never again under

Spanish control. This makes the Jivaro the only native group

to lead a successful uprising against their Spanish masters.

Their backlash against the conquistadors was so violent that

the word Jivaro soon entered the Spanish language with the meaning

"savage."

Because of outsider's fear of the Jivaro and the

remoteness of their dense, jungle territory, little was known

of them until the 20th century. What stories did come out, however,

were very frightening.

Despite their success on one occasion against

the Spanish, the Jivaro people never really united as a political

unit. Even though their customs, appearance, beliefs and culture

were very similar, they lived in small individual communities.

These groups were constantly at war with one another. While

around most of the world war is about gaining and controlling

territory, war for the Jivaro was about vengeance. Each killing

required retribution in a practice known as blood revenge.

The Jivaro feared that if they did not avenge the death of a

relative, then the spirit of that relative would be displeased

and cause all manner of bad luck for the tribe. In fact, the

Jivaro feared their own ancestors more than the spirits of those

whom they killed in their clashes.

During the raid of another village a warrior always

took care to retrieve the head of his victim by decapitating

it, passing a head band, or vine up through the throat, out

the mouth and then slinging it over his shoulder, allowing him

to make a rapid retreat. A raid might be considered a disappointment

even if several enemies were killed if no heads were recovered.

Making

a Shrunken Head

The practice of taking heads was common over much

of the world but the Jivaro added an extra step to the practice

through a process that creates what the Shuar tribe calls a

tsantsa.

|

Be

Careful What You Ask For...

There

is a somewhat apocryphal story told of a red-haired European

man who traveled into Jivaro territory as an agent charged

with the commission of bringing out an authentic dried

and shrunken human head. Eventually when the head was

shipped back to the buyer, however, it was strange in

that the tsantsa had not the usual dark hair of a South

American native, but a glorious crown of red hair…

|

To start the tsantsa process, the flesh is first

peeled away from the skull by making an incision up the back

of the neck. The skull itself and its contents are discarded

into a nearby river. The warrior then sews the eyes closed and

the mouth is sealed by the use of small, sharp palm pegs through

the lips. At this point the skin is put into a boiling pot and

allowed to simmer for between an hour and a half and two hours.

The solution in the pot includes a number of herbs containing

tannin, a compound that will preserve the skin. The length of

time in the pot is critical as too short a time will result

in the head will not shrinking properly and the flesh on the

inside of the skin not loosening. Too long in the pot and the

hair on top of the head will fall out.

When the head is taken out of the pot it will

have shrunk to about one-third of its original size and have

a rubbery texture. The skin is turned inside out and any flesh

still adhering to the inside of the skin is scraped away. The

incision at the back of the neck is then crudely sewn back up

and the skin turned right-side out.

The next step is the drying process. The head

will continue to shrink during this stage as it is turned upside

down and filled with small rocks heated by a fire. When the

head gets too small for the pebbles, hot sand, heated in a bowl,

is used. Hot rocks are also applied to the outside of the head

to help shape and maintain the features. It is important to

the Jivaro warrior to make sure that the final product resembles

the original victim. Even so, the faces on shrunken heads usually

have some distortion because the area of the lower face shrinks

less than the skin on the sides of the forehead, causing the

jaws to appear to jut outwards.

The use of hot rocks and sand to shrink and shape

the head lasts several days. After that the next steps are to

remove the pegs through the lips and replace them with dangling

cotton cords, rub ash into the skin, and finally hang the head

over a fire to dry and harden. When this is done the head can

then be attached to a cord through the scalp so that it can

be worn about the warrior's neck. The whole procedure takes

about a week and results in a miniature of the original head

with a much darker skin tone. At the end of this process the

warriors would hold the first of several tsantsa celebrations

to commemorate the successful revenge on the enemy.

Getting

the Enemy's Arutam

In addition to a spirit that survives death, the

wakani, the Jivaro believe that each warrior has magical

personal power called the arutam. A warrior can increase

his arutam by collecting heads in battle. In turn, should his

head be taken, the warrior who collects his head will benefit

from the original warrior's arutam. There is also a vengeful

spirit of the dead warrior, the muisak, that is thought

to be dangerous to the head's new owner and the shrinking process

is considered a way of restaining or destroying the muisak.

The eyes and mouth of the tsantsa are sewn shut in an attempt

to contain this spirit within the head and keep it from escaping.

Occasionally a head cannot be taken during battle.

Either the warriors are forced to retreat too quickly or the

victim is found to be a relative of the executioner (then taking

the head is considered immoral). In these cirmcumstances a substitute

tsantsa can be made from a sloth head. (The Jivaro believe that

men are descended from animals, particularly sloths).

|

A

head from the Science Museum in London. It has since been

withdrawn from display.(Credit Frankie

Roberto)

|

The

Shrunken Head Trade

In the late 19th century Europeans and Americans,

hearing stories about the Jivaro and their unusual traditions,

started buying shrunken heads as curiosities. The going rate

by the1930's was about $25 per head. The tribesmen soon learned

that they could obtain money or a firearm in trade for a tsantsa.

The use of guns led to an increased number of more deadly feuds,

which in turn created more heads for the trade. Because the

demand for shrunken heads by tourists was actually causing the

Jivaros to do more headhunting, the governments of Peru and

Equator enacted strict laws forbidding the buying and selling

of tsantsa in order to slow the slaughter. In the 1940's the

United States also banned the import of shrunken heads.

Fakes

With the demand for souvenir shrunken heads high

and the supply restricted by law, a counterfeit market soon

developed. Some were produced by using goat, sloth or monkey

skin fashioned into the shape of a human head. Experts trying

to determine if a head is a fake will look at the shape and

detail of the ears which are hard to duplicate.

During the early 20th century some counterfeit

shrunken heads were produced not by the Jivaro, but thousands

of miles away in Panama. These fakes often involved real human

heads taken from unclaimed corpses obtained at hospitals or

morgues. To tell these heads from authentic tsantsa experts

look for signs that the work was done by someone other than

a Jivaro. The Jivaro used heavy cotton string to sew the mouth

and back of the neck closed, not thin thread. On a true Jivaro

shunken head the lips also bear the marks of the wooden pins

used to seal the mouth during the preparation process. In general,

the work on a tsantsa appears much neater and cleaner when the

work is done by forgers, as the Jivaro did not have access to

modern tools and equipment.

Even with careful examination, however, connoisseurs

have been fooled by clever fakes. Some experts estimate that

most of the shrunken heads held in many museums today are not

real, but forgeries.

|

Shrunken

heads on display at Ye Olde Curiosity Shop, Seattle,

Washington. They are most likely a mix of real and fake.

(Credit Joe Mabel licenced through GNU

Free Documentation License)

|

Today, replicas of tsantas (usually made from

animal products) are still sold, but are clearly labeled as

fakes. Fortunately, the Jivaro tradition of making tsantsas

from real human heads is, hopefully, completely gone now. As

the 20th century wore on, missionaries penetrated the Jivaro

territory, Christianized them, and their extremely murderous

ways eventually departed. Now, though occasionally some sloth

heads are prepared in the tsantsa fashion, the warring to obtain

trophy heads is only part of a macabre history.

Copyright Lee

Krystek 2011. All Rights Reserved.