The

Hitler Diaries

|

Hitler

in Paris: Did he keep a diary?

|

It would have been one of the greatest historical

buys of the 20th century: Sixty-two handwritten volumes of a secret

diary kept by Adolf Hitler. Der Stern Magazine thought

they had the exclusive rights into one of the darkest minds of

all time. Instead, they paid millions of dollars for a hoax.

In the autumn of 1979 an investigative reporter

for the German magazine Der Stern, Gerd Heidemann, was

invited to the house of a man named Fritz Stiefel, a collecter

of Nazi memorabilia. Stiefel had paintings and letters created

by Hitler laid out in a glass case like a museum display. Heidemann,

a Nazi enthusiast, studied each of them carefully. Finally he

noticed something else in the case: A black book. When he asked

about it he was told that it was a secret diary kept by the Nazi

leader. One of supposedly six volumes.

Heidemann was shocked. He'd been fascinated by the

life of Hitler for years but never heard that the man had kept

a diary. The inner thinking of the Nazi leader had always been

a mystery even to other leading members of the Third Reich. A

true diary would give historians insight into the thinking of

a man who had, for evil, changed the face of the world. Heidemann

realized that if the diaries were authentic and if he could get

a hold of them, he would have one of the biggest journalistic

scoops of the 20th century. To buy the diaries Heidemann knew

he would have to have the economic backing of his magazine

Stern, but before they would give him the money he would have

to make a case for the diaries being authentic.

Tracking

the Diaries

One of Heidemenn's first steps was to try and determine

how the Stiefel's volume of the diary had gotten into his hands.

Stiefel had been told the diary had been aboard a plane carrying

some of the Fuehrer's belongings that had crashed in the village

of Boernersdorf at the end of the war. The first thing that Heidemann

did was to travel to Boernersdorf to confirm the story. There

he found that indeed there had been a plane crash in April of

1945. Records indicated that a Junkers 352 transport went down

carrying some of Hitler's personal effects. When he heard of the

crash Hitler had stated, "In that plane were all my private

archives that I had intended as a testament to posterity. It is

a catastrophe!"

|

A

German transport plane similar to the one that crashed in

Boernersdorf.

|

Heidemann also found that a chest of papers had

supposedly been recovered from the wreck and this was rumored

to be the source of the diaries. He also learned there were 27

more volumes of the diaries in the hands of a man named Konrad

Fischer.

Equipped with this information, Heidemann made a

proposal to his bosses at Stern that they purchase the

diaries. Stern said it would pay as much as 2 million marks

(approximately $800,000) to obtain the diaries. With this money

behind him, Heidemann went searching for Fischer. Fischer turned

out to be hard to find. Eventually Heidemann contacted him through

intermediaries. Fischer seemed reluctant to sell the diaries,

but the amount of money involved won him over. He did inist that

Heidemann promise to keep his identity a secret.

The first diary was delivered to Stern editorial

offices in January of 1981. Surprisingly more and more diaries

kept showing up. Heidemann told his bosses that after the plane

crash the diaries had come into the possession of an East German

general and were being smuggled out of that country one by one

(supposedly inside pianos). With each new volume Stern

paid more money and stood to make more money when they resold

the story to other news media. The final tally was 62 volumes

(covering the period from 1932 to 1945) for which Stern

paid 9.9 million marks (almost $4 million).

Before Stern could resell the story they

needed to make sure the diaries were authentic. To do this they

had handwriting experts compare the diaries with copies of material

found by Heidemann in the German Federal Archives at Koblenz.

Without question the handwriting was identical and Stern's

editors enthusiasm for the project soared, perhaps blinding them

to the need for additional authentication checks.

Breaking

the Story

|

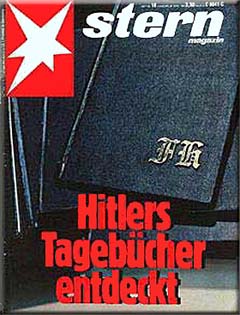

The

April 25, 1983 cover of the German magazine Der Stern.

|

On April 25th, 1983, Stern magazine broke

the story. The cover, showing one of the black bound volumes,

proclaimed "Hitlers Tagebucher Entdeckt" or "Hitler's Diary Discovered."

The news media around the world jumped on the story. Newsweek,

ParisMatch and London's Sunday Times and Times

newspapers all made bids to get the rights to reprint all or part

of the diaries. Stern stood to make a fortune on the reprint

rights.

What the diaries showed was surprising. If one were

to believe the diaries, Hitler was a much more kinder and gentler

man than the historical record showed. In particular, the diary

entries suggested that he had little knowledge of what was happening

in the concentration camps scattered around Europe. He also expressed

a desire to deport the Jews to other countries rather than put

them to death.

Even before skeptics got a look at the material

they expressed doubts that the diaries were real. Historians familiar

with Hitler pointed out that he loathed to write and that none

of his intimates in the Nazi organization, including his secretary,

had believed he had kept a diary. When the critics actually got

to look at the material their objections to its authenticity only

increased. Historian David Irving pointed out that what was recorded

in the diaries did not correspond to known historical events and

the materials that the books were composed of appeared to be too

modern for the era. Most damaging of all was the claim by experts

of Hitler's writing that the script in the diaries did not resemble

his at all, especially since the handwriting had been at the heart

of Stern's authentication procedure.

The

Hoax Revealed

West Germany's Federal Archives decided to get involved

and ran several scientific tests on the books. On May 6, 1983,

they released their findings: the paper, ink and glue of the diaries

was undoubtedly manufactured after the end of World War II and

Hitler's death. The volumes for which Stern had paid millions

of dollars were worthless forgeries.

Stern realized that it had been taken and

heads began to roll. Several members of the staff (including Heidemann)

were fired. In addition Stern's founder, Henri Nannen,

filed fraud charges against Heidemann several days later and the

police began to investigate. It quickly became clear that Heidemann

had not forged the diaries himself. Heidemann gave up Fischer's

name and the investigation soon focused on him. The police soon

discovered that Fischer's real name was Konrad Kujau. Kujau was

a petty criminal who specialized in forgery. He had started by

taking legitimate Nazi memorabilia and adding the names of important

Nazis to increase the value. Later on he started forging entire

works including letters, documents and even paintings and sketches

allegedly done by Hitler. In a 1983 book by Billy Price called

Adolf Hitler: The Unknown Artist a quarter of the works

pictured were actually forgeries by Kujau.

Kujau's prolific forgery solved the mystery of how

the Stern handwriting experts had been fooled. When they

had compared the handwriting in the diaries to the handwriting

found in letters by Hitler, they pronounced it identical. Indeed

it was. The letters that they had used for comparison turned out

to be previous forgeries by Kujau, not actually letters written

by Hitler.

Kujau, Heidemann and Kujau's wife, Edith, were brought

to trial. Kujau claimed that Heidemann was completely aware that

the documents were forgeries but bought them anyway paying 1 million

marks. Heidemann claimed he hadn't know they were forgeries but

admitted that he had seen the possibility of some historical discrepancies.

Kujau and Heidemann were given four and one half years in prison

and Edith eight months. The judge stated that while there were

only three defendants, the Stern's publishing firm should

be the fourth. He said that Stern had "acted with such

naiveté and negligence that it was virtually an accomplice in

the fraud."

Nobody ever found out what happened to the bulk

of the money paid out by Stern. According to Kujau, Heidemann

skimmed much of it before paying him. Clearly both Kajau and Heidemann's

lifestyle took a turn for the better at the time of the fraud

and most of the money never made it back into Stern's hands.

Could Stern really have avoided the loss

of millions of dollars and its international reputation? It seems

clear in retrospect that the publishing firm could have found

out the truth if they had simply subjected the diaries to a few

scientific tests. Examination of the books themselves showed that

they contained whiteners and threads not manufactured until the

1950's. Chemical tests revealed that the ink was modern and only

recently applied to the paper.

A careful reading of the text would have also revealed

historical inaccuracies that might not have proved the diaries

fake by themselves, but should have raised suspicions. Much of

the material Kujau stole from a book called Hitler's Speeches

and Proclamations written by Max Domarus. This also should

have raised a red flag to anyone carefully trying to authenticate

the diaries.

As the judge indicated, the owners and editors of

Der Stern may have been as much to blame as Kujau and Heidemann.

They were too ready to believe that they had scooped every news

organization in the world on the the story of the Hitler diaries,

and much too ready to profit from it.

A

Partial Bibliography

Selling Hitler by Robert Harris, Pantheon Books,

1986.

The Hitler Diaries: Fakes that Fooled the World by Charles

Hamilton, The University of Kentucky Press, 1991.

The Hitler Diaries, a Notorious Case of Forgery, The Crime

Library, (http://crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/hitler_diaries/index.htm),

2005.

Copyright 2005,

Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved.