pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Custom Search

|

|

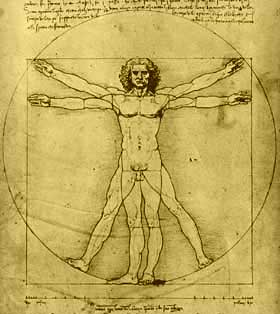

Leonardo's NotebooksThe great artist Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks probably started out as just a way for him to improve the quality of his paintings. He studied anatomy to portray the human body accurately. He studied plants and rocks to make them authentic for his paintings. Somewhere along the line, however, the books became more than that. They became a record of his life-long fascination with nature and his genius for invention. At the time of his death in 1519 Leonardo was known as a great artist, but his capabilities as an engineer, scientist and inventor were less appreciated. After his demise, his notebooks fell into the possession of his favorite apprentice Francesco Melzi. Melzi held onto most of them and kept them safe until his own death in 1579. Melzi heirs had less respect for the material, however, and sold pages off to collectors or gave them away to friends. In 1630 Pompeo Leoni, a sculptor in the Court of the King of Spain, got a hold of much of the material and tried to organize it by subject. This unfortunatley resulted in the books being taken apart and the original order, which might have told us much about Leonardo's thinking, was lost. Each of the new books created by this process was a Codex.

In many of his books Leonardo employed a backwards form of writing that could only be read with a mirror. It is unknown why he did this. Some historians speculate he did it to keep his writings private, others think that because he was left-handed he just found it easier and faster to write this way. Clearly the notebooks were written for his own personal use. The organization is minimal. The lettering is quick, sloppy and often without punctuation. There is some indication he employed a personal shorthand, making the content confusing to read. In many places the pen seems to race along trying to keep up with the revelations of the mind. Much of the books appear to be lab notes. Leonardo used the scientific method before the scientific method had been invented. In one revealing passage he states, "First I shall make some experiments before I proceed further, because my intention is to consult experience first and then by means of reasoning show why such experiment is bound to work in such a way. And this is the rule by which those who analyze natural effects must proceed; and although nature begins with the cause and ends with the experience, we must follow the opposite course, namely (as I said before), begin with the experience and by means of it investigate the cause." Over time most of the notebooks have found their way into various museums, archives or libraries around the world. Only one is in private hands. Two were totally unknown until 1966 when they were found by chance in the National Library of Madrid. Presently there are ten known codices containing Leonardo's sketches and notes.

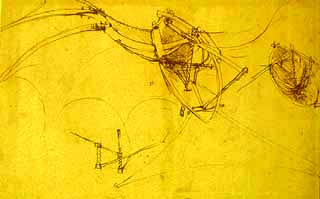

Codex Atlanticus - This document contains information on mathematics, geometry, astronomy, botany, zoology and the military arts. It is held by the Biblioteca Ambrosianain in Milan, Italy. There are some 1,119 pages in this work spread over 12 volumes. This sketchbook contains some of Leonardo's most famous drawings and notes. Of particular interest are the pages on gliders and flying machines. Most of Leonardo's aerial machines were designed after he studied birds. For this reason they generated their forward motion by mechanisms designed to flap the wings. In his notes he recorded, "the bird is an instrument functioning according to mathematical laws, and man has the power to reproduce an instrument like this with all its movements." He built a working model of one of his flying machines and on January 2, 1496, he recorded in his notes that he was going to attempt to fly it the next day. It is unknown whether he didn't try or if the flight was a failure. Later on he did make a note to himself to try any more flying experiments over a lake where he would be less likely to be injured in a landing. Atlanticus also contains a design for a parachute which might have been conceived to allow for the safe escape of any pilot from a flying device.

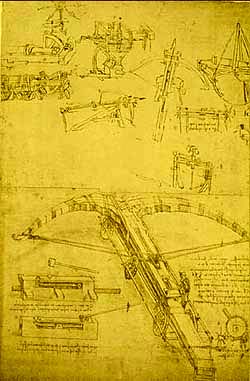

Atlanticus also contains a number of military designs including those for a giant crossbow and a compact version of a wooden spring catapult designed to hurl boulders. There were also siege machines created to defeat city walls and span moats and designs for castles and fortifications. Codex Arundel - This book resides in the British Library in London and is one of the ones created by the cutting and pasting of pages from other works. Most of the material deals with the study of geometry, weights and architecture and the pages seem to have been authored between 1480 and 1518. Among other items, the Arundel document contains a design for a primitive tank that resembles a flying saucer as well as plans for an underwater diving bell. Codices of the Institute of France - These are twelve documents (referred to as A-M) of varying sizes that cover a variety of areas including hydraulics, military art, optics, geometry and bird flight. One of Leonardo's most well known-designs, a primitive helicopter, is included

in manuscript B. The device was designed to be operated by four men. The men would never have had the strength necessary to create sufficient lift, but if a suitable engine had been substituted it might have actually gotten off the ground. Codex Trivulzianus - There are only 55 pages in this document currently held in Milan. The subjects of this collection include religion, architecture and literature. It is thought the pages in this work were composed between 1487 and 1490. Codex "On the Flight of Birds" - This short work of only 17 pages is a very careful study Leonardo did in 1505 on the mechanics of flight and the movement of air. Codex Ashburnham - This is actually composed of two documents held by the Institute of France. It primarily consists of pictorial studies drawn between 1489 and 1492. Codex Forster - These are three different documents held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. They are composed of studies about geometry, weights and hydraulic machines. Written between 1490 and 1505,

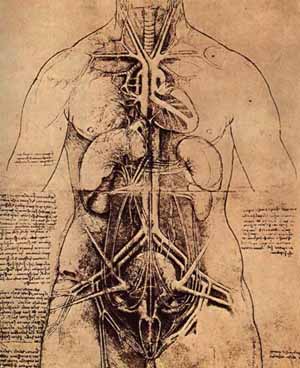

Codex Leicester - This manuscript was in the news when it was purchased by Bill Gates in 1995 for $30.8 million. It contains 64 pages mostly dedicated to Leonardo's theories on astronomy, the properties of water, rocks and fossils, air and celestial light. It is currently exhibited in the Seattle Museum of Art. Windsor Royal Documents - These pages are part of the royal collection at Windsor Castle. The subjects include anatomy and geography, horse studies, drawings, caricatures and a series of maps. There are about 600 unbound pages created between 1478 and 1518. The Madrid Codices - These manuscripts were found in the archives of the National Library of Madrid. There are two volumes bound in red morocco leather and contain 197 pages on geometry and mechanics. |

|

Related Links |

|

|