The Mandela

Effect: Are Alternative Universes Colliding?

|

Nelson

Maldela alive in 1998.

|

Is this a serious scientific enigma, or just another

internet conspiracy theory?

A few years ago in the late 2000's Fiona Broome,

a writer and self-described paranormal researcher, was surprised

to find that Nelson Mandela was still alive. Mandela, a South

African human rights activist that had spent many years in jail

and later became president of the country, died in 2013, but

Broome had vivid memories of him dying in prison in the 1980's.

As Broome recalled:

See, I thought Nelson Mandela died in prison.

I thought I remembered it clearly, complete with news clips

of his funeral, the mourning in South Africa, some rioting in

cities, and the heartfelt speech by his widow.

Then, I found out he was still alive.

At first Broome chalked this up to a faulty memory,

but later, while hanging out at Dragon Con (an Atlanta Science

Fiction and Comic book Convention) she met a number of people

who seemed to have the same memories.

Broome became interested enough in the phenomenon

that she launched a website and quickly discovered that many

other people seemed to have memories of past events that didn't

seem to jive with the history books. She called this experience

The Mandela Effect.

The

Berenstain Bears

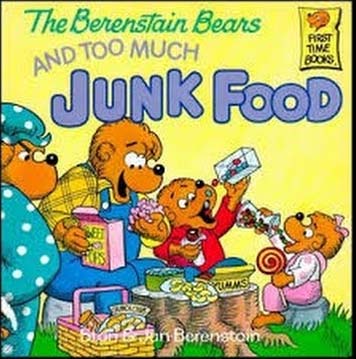

Probably the most well-known example of the Mandela

Effect is the case of the Berenstain Bears. The Berenstain Bears

was a children's book series launched in 1962 and written and

illustrated by Stan and Jan Berenstain. The series was widely

read and loved by several generations of children. The Mandela

Effect comes into play because many, if not most people, remember

the series when they were growing up being spelled the Berenstein

Bears, with an "e" instead of an "a."

In fact, a number of people have claimed to have

materials - VHS tapes and screen captures of websites - showing

the "a" instead of the "e."

Another popular example of the Mandela Effect

is the logo for the Ford Motor Company. According to historical

records the logo has always featured a curl at the end of the

crossbar in the "F" character. However, many people, don't remember

it that way and believe it has somehow been changed.

|

The

Bears series: Berenstain or Berenstein?

|

Ford isn't the only company logo that supporters

of the Mandela Effect alleged has been changed. They point to

the "Jiffy" peanut butter product. Lots of people remember "Jiffy"

but I you won't find it on any supermarket shelf in the United

States. That's because the product is actually "Jif" not Jiffy.

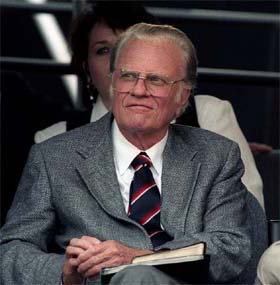

In another case of a celebrity death, many people

seem to remember the preacher Billy Graham's demise and seeing

his funeral on the television. However, as of this writing,

the Reverend Graham is still alive and though aged, is still

with us.

So what is happening here? Do people just have

bad memories, or is something else going on?

Alternate

Universes

Broome and other supporters think that maybe a

collision of alternate universes is to blame. They believe that

there are many universes, each one slightly different from another

(for example, in one universe the book series is spelled "Berenstain

Bears" and in another it's "Berenstein Bears"). When these universes

come together the past gets mixed up allowing people to remember

the spelling in alternate ways.

As crazy as this sounds, science does suggest

that there may be multiple universes. The "many-worlds interpretation"

of quantum mechanics resolves some odd aspects of that theory

by suggesting there may be a very large (perhaps even infinite)

number of universes, and everything that could possibly have

happened in our past, but did not, has occurred in the past

in one or more of the other universes.

However, there is no evidence that these multiple

universes (if they do exist) can interact with each other in

a way to produce the Mandela Effect.

Another theory held by supporters of the Mandela

Effect is that we are living in a virtual world (similar to

the one dramatized in the movie "The Matrix") and the Mandela

Effect is the result of changes being made to this virtual world.

While both the "many-worlds interpretation" and

the "virtual world" theory are intriguing ideas, they

are beyond our ability to test in any scientific way. They also

seem unsatisfactory solutions to the question of the Mandela

Effect because they fail a scientific rule-of-thumb known as

Occam's Razor.

Occam's

Razor

Occam's Razor is a problem-solving principle attributed

to William of Ockham who was a fourteenth century English Franciscan

friar, scholastic philosopher and theologian. The principle,

stated in layman's terms is ""the simplest explanation is usually

the correct one."

If we apply Occam's Razor to the Mandela Effect

we have to ask if multiple universes or is a faulty virtual

world the simplest solutions to the conundrum, or are there

other more straightforward possibilities? Or as the astronomer

Carl Sagan often asked, don't "extraordinary claims require

extraordinary proofs?"

Scientists know that people's memories can be

faulty. In fact, among police experts its well-known that eye

witness accounts are the least accurate type of evidence, even

though they are often the most persuasive to juries.

Why is this? We like to think our brains record

our experiences like a video camera records the world. When

a video recording is played back we can expect that unless the

recording has been tampered with, we are seeing the world exactly

as the camera saw it. The problem is that our minds are not

mechanical recording machines. Our brains have limited storage

space and only things that are important are recorded long term.

Try to remember what you had for breakfast two weeks ago last

Tuesday. Most people (unless they have the same thing every

Tuesday) can't.

Memories are also unlike video recording because

every time we access a memory there is really, really good chance,

given the way our brains store this information that we may

change the memory a bit. Think of the fisherman that each time

he tells the story about "the big one that got away" the fish

seems to get a bit larger.

Confabulation

The combination of these two effects result in

something referred to as "Confabulation." When we don't have

a complete memory we fill in the missing parts with something

that seems logical to our brains and because of the way our

brains are wired this can result in the original memory being

changed a bit.

How would confabulation account for something

like the "Berenstain Bears?" One of the things that people don't

store in their brains all the time is unusual spellings, especially

if the spelling isn't important to the overall memory. While

reading a Berenstain Bears book people would be much more likely

to remember that storyline than notice and remember that the

spelling of the name was a bit odd. When they try and remember

the spelling of the name their brains just fill in the most

common spelling which is with an "e" instead of the "a". The

source of this "Mandela Effect" is much more likely a false

memory than some clash of alternate universes.

|

Billy

Graham is not in the public eye, but still alive as of

Feburary 2017.( CC BY 2.0 Paul M Walsh).

|

Making the "Berenstain Bears" case even more complex

is that there have undoubtedly been instances were official

Berenstain Bears materials have been misprinted with the incorrect

spelling simply because the writer and editor failed to check

the proper spelling and assumed the more popular "Berenstein"

was correct.

Confabulation may also explain other Mandela Effects.

For example, while the Reverent Billy Graham is still alive,

his wife, Ruth Graham died in 2007, and her death was covered

in some TV news. People may be connecting her funeral, with

his decision to retire from his famous crusades in 2005. Knowing

that he has been out of public life and seeing news coverage

of her funeral they may have confabulated the two together to

assume his death.

It seems much more likely that Mandela effect

is a trick of our own memories than a collision of universes

or a virtual world. It also suggests that our individual memories

aren't particularly bad as so many people seem to remember certain

event wrong. It simply shows we are human and our memoies, as

much as we would like them to be perfect, are not.

Copyright Lee Krystek 2017. All Rights Reserved.