pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Notes from the Curator's Office: Of Automatons and Automata

(6/11) Every year or so, I spend a few days teaching a unit on puppetry at the college where I work. Puppetry is a fascinating art that has been practiced all over the world for thousands of years. What is conjured up in most people's minds when you say the word "puppets," however, are those Jim Henson creations that we have all grown up watching on Sesame Street. Though the Henson Muppets are beloved icons of the art, they only represent a tiny fraction of the type of puppets that exist. When a day was added to the class schedule this year, I decided it would give my students and myself the opportunity to explore a fascinating form of puppetry that is often ignored by most texts on the subject: Automata. Automata are puppets that are not controlled by people. They are mechanically driven. Today we might even refer to them as robots, though this is really a term that was only invented in the 1920s. The history of the automaton (the singular of automata) goes back much, much further. I would also separate robots from automata based on how they work. Most robots, both fictional and real, use both mechanical and digital electronic systems to operate. For the purposes of this article I'm going to define automata as machines that appear as human or animal using only mechanical systems with little or no electronics. Mechanical systems have been around a long time and for this reason, so have mechanical puppets. In fact, we need to go back to ancient Greece to really find the beginning of the automata story Talos and the Greek Machines

Even the ancient Greeks were fascinated with the idea of a machine that looks and acts like a man. At first, though, the power to make such a device seemed only to reside with the gods. Hephaestus, the god of volcanos and technology (called Vulcan by the Romans), built a number of mechanical beings in the shape of both humans and animals. Perhaps his most well-known mechanical man was a bronze giant named Talos. In the story Argonautica, Talos guards the island of Crete by tossing boulders at any unfriendly ships that approach. The legend has it that Talos had a vein that ran through his body filled with a blood-like fluid and sealed with a nail. When the nail was removed, the fluid ran out and Talso was destroyed. One of my favorite films, Jason and the Argonauts, depicts Jason knocking off Talos via this method during a scene filmed using Ray Harryhausen's glorious stop-motion photography special effects. The tale of Talos is clearly mythical, but there is reason to believe that the Greeks did actually create automata figures. Accounts indicate that Architus of Tarantum constructed a flying mechanical dove in the 5th century BC. Philon of Byzantium made several figures capable of simple actions including a maid that would fill a cup with a mixture of wine and water when the vessel was placed in her hand. It is also thought that the Greeks created automaton statues for their temples and religious ceremonies. Hero of Alexandria, who lived during the first century A.D., was an inventor credited with the creation of many devices including the first vending machine (it dispensed holy water when the buyer dropped in a coin). Hero supposedly created a whole automata theater that gave a performance ten minutes in length. According to accounts, the device was controlled by a series of ropes with knots tied in them. As the rope was pulled through the device, the knots moved levers which caused actions to happen on the miniature stage. The ancient city of Rhodes was renowned for its automata and a quote from the poet Pindar tells us:

For many years historians doubted the Greek's ability to create complex mechanical devices. However, in 1901, an incredibly-complicated apparatus was recovered from the wreck of an ancient Greek ship. The machine, given the name the "Antikythera mechanism" based on where it was found, clearly used an array of complex gears to predict the movements of the planets and moon. This suggests the Greeks were much better technologists than most people had thought. Islamic Automata There is evidence while fewer automata were made in Europe with the onset of the Middle Ages, much of the knowledge about them was passed onto Muslim scholars who further advanced the work. Al-Jazari, an Islamic scientist, engineer and writer, described a number of automata in his 13th century Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. In the book Al-Jazari describes how he built a number of such devices including a band of mechanical musicians. These four, melodic automatons were positioned in a boat and were used for entertainment during royal gatherings. Al-Jazari also writes about a clock in the shape of an elephant that included automata figures: A man who strikes a bell and a bird that chips to mark the passage of time. Al-Jazari is credited with introducing many of the features that appeared in later automata and other mechanical devices. He often used the flow of water to power the machines and controlled their motion through the use of a camshaft. A camshaft is a rotating rod on which is mounted a series of cams. Cams are irregularly-shaped discs. As the camshaft turns, levers or pistons pressing against the cams move in and out in a pattern depending on how the cam is shaped. In an automaton the cams and camshaft operate as a sort of programmable memory. Each lever pressing against the cam can control one aspect of the machine's movement. Since the camshaft can have any number of cams on it, it can be used to coordinate the movement of a very complex device. While camshafts are particularly useful for automata, they are common features in many types of machines even today. Every internal combustion engine features at least one camshaft to control the movement of the valves that let gases move in and out of the cylinders. Clocks, Lions and Other Toys When automata did start showing up in Europe again it was often in the form of city clocks similar to Al-Jazari's elephant clock. One of the best known of these clocks was the Prague Astronomical Clock in the capital of the Czech Republic. It was installed in 1410 and still operates today. Legend has it that the maker, a man named Hanu, was rewarded for his excellent work by the town fathers by being blinded so that he could never reproduce the device for another town. Fortunately, this is just a colorful myth. The clock was originally built by clockmaker Mikulá of Kada and Professor Jan indel, a teacher of mathematics and astronomy at Charles University. Originally the clock had dials that showed the time and the position of the stars visible in the sky. Later in 1490 a calendar dial was added along with a number of automata figures. These included the twelve apostles and the figure of death in the form of a skeleton that strikes a bell to ring out the time. Mr. Skeleton was apparently a reminder of how short life is and to use your time well.

Many towns commissioned clocks with automata figures for their town halls, though few were as complex as the one in Prague. As Europe moved into the Renaissance, more and more automata appeared. Leonardo da Vinci designed a mechanical knight that could stand, sit, raise its visor and move its arms. He presented his creation at a celebration hosted by Duke Sforza at the court of Milan in 1495. Plans for the device were discovered in one of Leonardo's sketchbooks in the 1950's and the automaton has been recreated by engineer Mario Taddei. Leonardo also built at least two automata lions. The first, presented to French King Louis XII in 1509, could rear up on its hind legs and present lilies, the French royal symbol. A second lion could walk under its own power and move its head. It was a gift to François I when he visited Lyons in 1515. The side of the mechanical beast would pop open and give the king, again, lilies. François I was so impressed with the work he invited Leonardo to move to France to be the court painter, philosopher, architect and engineer. Leonardo spent the rest of his life working for the French king in relative comfort. Like the lions, many automata became playthings for the rich. A mechanical galleon made of copper and steel built by Hans Schlottheim of Augsburg in the 15th century was designed to sail up the dinner table to announce a banquet. The device has a number of moving figures including sailors who used hammers to strike the hours and quarter hours on bells. As it rolled along it would play music and in a grand finale the ship's cannons would fire. The device no longer works, but can still be seen at the British Museum in London.

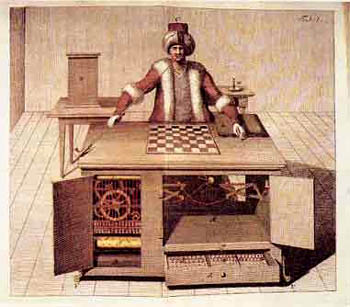

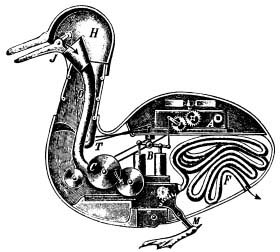

Hero's idea of a mechanical theater re-appeared in this era. These devices were often powered by windup springs or water. They might present several acts with a curtain closing in between or simply a continuous pageant of activity. One of the few from that era still operating is The Mechanical Theater of Schloss Hellbrunn which was installed in the Hellbrunn water gardens in Salzburg, Austria, in 1750. The theater depicts life in the town: workers carry goods, guards do their rounds and nobles stroll around, all to the tune of a water-powered organ. Some automata was constructed in an attempt to understand the operation of living animals. In 1739 French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson built a device he called the Canard Digérateur, or Digesting Duck. The automaton in the shape of a duck would appear to eat kernels of grain and later defecate the remains. The duck was actually a bit of a trick, however. It stored the eaten grain in one compartment while the feces it produced came from material stored in another compartment. Even though the duck didn't really digest anything, it demonstrated Vaucanson's belief that animals were just a complex type of machine whose muscles and bones could be replaced by gears and pistons. Henri Maillardet's Machine Perhaps the most complicated device from this period that still works is housed at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, USA. This science museum is the closest one to where I grew up and I remember visiting it on a number of class trips. The automaton appears as a mechanical boy sitting at a desk holding a pen. Though it never worked during my visits, it was still fascinating to look at and was my first introduction to an automaton. The device was built in the 18th century by Henri Maillardet, a Swiss clockmaker and mechanician who lived in London. When wound up with a key and paper was placed before it, the automaton could draw one of four different pictures or write one of two poems. It was a marvel of its time. Maillardet used the camshaft first conceived by Al-Jazari centuries before to control the motion of the figure's hand. Maillardet demonstrated his machine around London in the early 17th century, but after 1833 nobody is sure what happened to it. There are rumors that it may have been purchased at one point by showman P.T. Barnum and brought to the United States. The Franklin Institute obtained it when in November of 1928, a truck pulled up to the museum and unloaded the pieces of a ruined brass machine that had been destroyed in a fire. They had no idea of its origin. It took many decades for the staff and volunteers at the museum to get the device working again. When they finally switched it on they watched in amazement as it drew out one picture and signed it "Written by the Automaton of Maillardet:" the first clue they had to its creator. "The Turk" Pulls a Fast One Probably the most well-known automaton of the 18th century was a mechanical chess playing machine called "The Turk." The Turk was constructed in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen, a Hungarian author and inventor. The device appeared as a life-sized man's torso sporting a black beard and a turban, giving the machine the appearance of an oriental sorcerer. In front of the machine was a large desk on which sat a chessboard. When he demonstrated it, Kempelen would open the front of the desk to show the many complex gears and cams needed to operate the machine. The Turk toured the world, winning games wherever it went against some notable opponents like Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. It wasn't until the 1820s that the machine was exposed as an elaborate hoax. Concealed within the base of the mechanism was a human chess expert, his location disguised by a clever arrangement that allowed him to change positions inside the desk so that he was always in a part of the desk which had its doors closed. In this way the demonstrator could open every door the machine had for inspection (just not all at the same time) and never give the trick away. Of course today we have digital computers capable of playing chess games at the highest level. If these were connected with a robot to move the pieces a real version of The Turk could be made. With most of its smarts in digital-electronic form, however such as device would be outside my definition of automata I gave earlier. Is there any room in our high-tech, digital, electronic world for such quaint devices?

Modern Automata Automata certainly exist in our world today. The real pioneer of these modern versions was Walt Disney. Disney didn't call his inventions automata, but actually trade-marked the name "Audio-Animatronics" as he saw them as a three-dimensional extension of animation. Disney's first major automata attraction was The Enchanted Tiki Room, which opened in Disneyland in 1963. The room was filled with mechanical birds and flowers that talked and sang. I saw it as a child in the late 60's and was fascinated. I still think of it as one of Disney's best attractions. The Disney people have often talked about their devices as being under computer command, but the truth is that the early ones, like the Tiki Room, had no digital circuitry at all. For example, to make a bird open his beak a valve would be opened in the attraction's control center that sent pressurized air up a small tube to the artificial animal. The pressure would then push a small piston connected to the bird's beak making it open. The tube could run a great distance from the control room allowing the controls to be quite some distance from the puppet. The tubes were small enough that several could be threaded up the bird's leg to give it a number of possible movements. The valve was controlled by an electrical switch that responded to a certain tone. The tones were placed on an audio tape with several other tracks that also included the music and singing. By simply playing the tape, the whole show would be set in motion with everything perfectly coordinated. Disney isn't the only one who has automata figures. They are found in a number of entertainment and educational venues (one of my personal favorites are automaton dinosaurs). Automata figures are still found in clocks these days. The Nippon Television Network headquarters in Japan has a 28-ton mechanical clock that features dozens of automata figures and is the largest of this type of device in the world. My favorite modern application of automata comes in the form of smaller art work, however. In particular I find the work of Thomas Kuntz very interesting. He's built a number of automata instillations ranging from the complex "The Alchemysts Clocktower," which is really a five-minute automata theater presentation, to the simple but engaging "The Great Kundalini, Thelemagician" where an evil sorcerer levitates an unwilling victim.

Although creating such complex mechanical puppets as Kuntz does is beyond the capability of most of us, there are a number of simple automata anybody can build. A basic wooden automaton can be built from a kit. I purchased a book which allows you to punch out cardboard pieces and glue them together to make hand-cranked models of leaping sheep and a flying fish. They made excellent demonstrations for my class. The Exploratoriam, an amazing hands-on science museum in California, has downloadable instructions for several simple automata that can be built out of cardboard. So take some time to explore mechanical puppets. It's a fascinating history. Copyright Lee Krystek 2011. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|