pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Notes from the Curator's Office The Big Three: Robert Heinlein

This is the second of three articles reviewing the work of the "Big Three" science fiction authors of the 20th Century. (8/07) Of the Big Three, science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein is probably the most enigmatic. To readers of his work he sometimes appears to speak as a flaming liberal, at others times a reactionary conservative with politics a little to the right of Darth Vader. To make things even more complicated, the real Robert Heinlein was not an easy man to get to know because of his strong feelings about privacy. Last month marks the 100th anniversary of Heinlein's (which is pronounced Hine-line) birth on July 7, 1907. He was born in Butler, Missouri, the heart of the American Mid-west. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1929, reaching the rank of lieutenant before he was discharged 1934 because of a bout with pulmonary tuberculosis. Heinlein always had an engineering mind and while he was forced to remain in bed convalescing, he came up with the idea of the waterbed which he later described in his books. After a brief try at politics, Heinlein decided to try and earn some money by writing. In 1939, his first story, Life-Line, was published in Astounding Science-Fiction magazine. During World War II he worked at the Philadelphia Naval Yard doing aeronautical engineering. This activity put him in close contact with another of the Big Three members: Isaac Asimov. He also worked closely there with L. Sprague de Camp, who was to become a major science fiction and fantasy author over the next several decades. One can't help but wonder what the lunch time repartee was like.

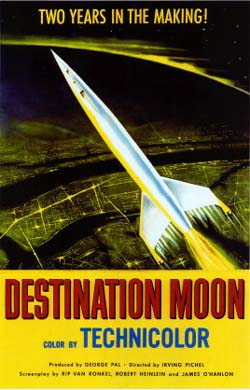

After the war Heinlein became the first science-fiction writer to move from pulp magazines to more general publications like the Saturday Evening Post. Most of Heinlein's work was "hard" science fiction - a subset of the genre which emphasizes technical detail and scientific accuracy. Typical of this was a project he got involved in 1950 called Destination Moon. This was a documentary-type exercise about what the first trip to the moon might look like. Heinlein conceived of the idea, co-wrote the script and even invented many of the special effects for the film. In fact, the effects he helped engineer were so ground breaking that the picture was given an Academy Award. Heinlein's Juveniles Starting around that time Heinlein also worked out an arrangement with Charles Scribner's Sons Publishing. Each year for the Christmas season Heinlein would produce a novel for the juvenile market. Heinlein's Juveniles, as they are called, are some of his best, and certainly most influential, works. Thousand of teenagers, who eventually became engineers and scientists, grew up reading these books. The first of this series of twelve was Rocket Ship Galileo, published in 1947. It told the story of a group of teens who retrofit a rocket ship to go to the moon.

Typical of the series is number six, one of my favorites, The Rolling Stones. This book is about the Stone family who live on the moon in the distant future. The family's twin sons convince their father to purchase a slightly-used spaceship, refurbish it and go cruising around the solar system, visiting such places as the asteroid belt and Mars. On the red planet they pick up a native form of life called a "flatcat" which multiplies out of control once back aboard the ship. Science fiction enthusiasts will recognize this incident as similar to the plot of the Star Trek episode The Trouble with Tribbles. It was so similar, in fact, that it was necessary for producers to get Heinlein to agree to sign a waver before the episode could be filmed. Heinlein took pains in each story to discuss the engineering aspects of many of the devices used by the protagonists. In the last book in the juvenile series, Have Spacesuit - Will Travel, he spends considerable time in allowing the narrator, Kip, to explain the function and repair of a spacesuit which Kip has won as part of a publicity contest. This attention to detail shows Heinlein's engineering background and undoubtedly engaged the interest of many of his readers who went on to become engineers themselves. This type of technical detail can be seen throughout much of Heinlein's works, though critics complain that it often slows down the story. The juvenile stories were actually read and enjoyed by many adults, too. In Have Spacesuit - Will Travel, Kip, a high-school senior, finds himself an unwilling passenger on his way to Pluto when he attempts to rescue a nine-year-old girl kidnapped by alien invaders. Their adventures involve such diverse activities as stealing a flying saucer, making a desperate run across the surface of the moon under threat of asphyxiation, and standing on trial in an inter-galactic court defending all humanity against annihilation. Heinlein respected his young audience and always pushed the limits of juvenile fiction by including themes and concepts that were designed to stretch teenage thinking. The series ended when Heinlein, in the opinion of his publisher, pushed juvenile fiction too far by writing a novel about infantry men of the future caught in a vast interplanetary war. The book, Starship Troopers, was eventually printed by another publisher and quickly became one of Heinlein's most successful, though controversial, novels.

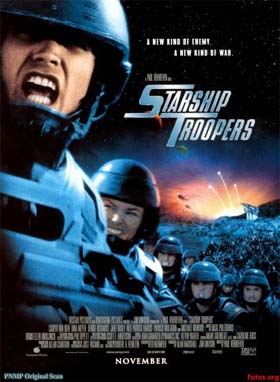

We are now at a point where it probably makes sense to discuss Heinlein's political leanings. In his earlier years, Heinlein seems to be a liberal and was in fact at one point a member of a Socialist party. By the Reagan era, however, he appears to have transformed into a staunch conservative. The truth is that Heinlein is almost impossible to pin down to one portion of the political spectrum. Throughout most of his life, however, he seems mostly to have adhered to libertarian philosophy: people should be able to live their life as they wish as long as they give others the right to do the same. StarShip Troopers Starship Troopers, though labeled a novel about war, actually spends a lot more time talking about philosophy. In it, Heinlein allows his characters to express some of his ideas about suffrage (only those who have volunteered service to the government, like two years in the infantry, are allowed to vote), war ("violence has settled more issues in history than has any other factor.") and democracy. (They fail because "people had been led to believe that they could simply vote for whatever they wanted... and get it, without toil, without sweat, without tears.") Most people are only familiar with the book through Paul Verhoeven's 1997 film version of Starship Troopers. That project, however, did not start as a film version of Heinlein's book, but the title, characters and some of Heinlein's ideas were added later. For this reason most fans don't like the film. I have to admit, however, that I'm surprised how much of his ideas actually did find their way into the film. The society pictured in the movie is much like that described in the book. Voting franchise is extended only to those who have given two years of service to the government (usually military service), corporal punishment is used sometimes instead of a penal system, and the attitude of the film seems decisively pro-military. These ideas bothered a lot of people and I suspect that they bothered Verhoeven also (in fact, Verhoeven has stated that he did not even finish reading the book as he found it too depressing). The result is that while a lot of Heinlein's ideas are here in the movie, Verhoeven, perhaps as a protest, has also incorporated uniforms and propaganda-like material into the film that is vaguely suggestive of the Nazi era (though a Nazi Germany without sexual or racial discrimination). I have to say that the final results (in addition to be a decent action flick) are at least somewhat thought-provoking.

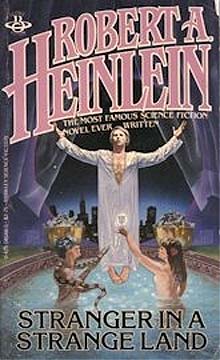

What was completely left out of the movie, however, is any of the technological innovations Heinlein put in the book. The Mobile Infantry of the book as envisioned by Heinlein was a strike force parachuting out of orbit and directly down to the surface of the planet. Troopers were equipped with powered armor giving them super strength, electronically-extended senses (night vision, etc.), and the ability to leap tall buildings in a single bound. This effectively made Heinlein's troopers walking, one-man tanks. None of these innovations showed up in the movie, but they did not escape the notice of the Pentagon which researched some of these ideas extensively. While the military has yet to produce a suit of powered armor that is practical, things like night-vision goggles and GPS positioning systems are now standard military equipment. Also, the concepts espoused in the book, that soldiers should be a high-tech strike force, are now echoed in actual military service policies. The book is on the reading list of all the U.S. military academies. Starship Troopers created a whole new sub-genre: the science fiction military novel. It was also terribly controversial and seen by many as a glorification of war and militarism. Some, like Verhoeven, have looked at the society Heinlein portrays in the book and found it fascist. In any case, as I noted before, the publisher, Scribner, felt that it didn't fit the juvenile series and the relationship with Heinlein ended. This was fine with Heinlein, who was tired of being seen as just a young person's author anyway. Stranger and Stranger At the same time Heinlein was working on Starship Troopers, he was also writing what is probably his best-known work Stranger in a Strange Land. Stranger in a Strange Land is the story of Valentine Michael Smith, the child of two astronauts that disappeared on a failed expedition to Mars. Smith is raised by Martians and returned to Earth as an adult. Initially Smith understands little of Earth customs and culture. Eventually, however, Smith "groks" (the Martian word for understands) people and founds his own religious cult.

Heinlein's editors insisted he cut the book from about 200,000 words to 160,000 words, removing many scenes and ideas that would have been shocking to the public when the book was first released in 1961. This is the first book where Heinlein's unconventional ideas about free love, group sex and nudity emerged. Stranger in a Strange Land soon became a favorite novel of the 60's anti-war counterculture, despite the fact that ironically it had been written by the same man who had simultaneously produced the militaristic Starship Troopers. In 1966 Heinlein produced The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, the story of an unlikely set of future revolutionaries led by a sentient computer that sets the lunar colonies in rebellion against mother Earth. This book probably is the best representation of Heinlein's beliefs as the storyline allows him free reign to discuss his ideas about government, society and family. The lunar colonists, mostly convicted criminals or political exiles, create a society with little government, save the despotic "lunar authority" controlled from Earth. There is no real need for police or a jail on the moon as misbehavior is punished by simply tossing any offender out of the nearest airlock. Typical family arrangements in Heinlein's world disappear in favor of marriages involving multiple husbands and wives. Even with these strange societal twists, however, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress remains a work of hard science fiction - the technology is plausible and well thought-out. After 1980, a period that followed a serious illness, Heinlein's work took a more fantasy-like turn. The adventure stories of an earlier era taking a backseat to his unorthodox philosophies. These final novels, which include The Number of the Beast and The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, are extremely controversial especially with many of his fans who originally fell in love with his juvenile work back in the 1950's. One issue Heinlein always felt strongly about and championed in his final years was racial equality. Heinlein often challenged readers' racial stereotyping by introducing a character, letting the reader get to know the character, then only much later on giving a physical description that included the character's race. Heinlein also strongly denounced racism in his non-fiction works. Heinlein Legacy

As he grew older Heinlein suffered a series of serious health problems and on May 8th 1988 he died of emphysema and congestive heart failure. However he left behind a legacy of engaging and thought-provoking works: 32 novels and 59 short stories. (A full list of his works can be found here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_A._Heinlein_bibliography) Another three non-fiction novels were published posthumously. I have to say that of all his works, I still enjoy his juvenile series the best. Even though it originally came out in the 1950's, they still remain as exciting and challenging for young readers as ever, while at the same time having the maturity necessary to hold adult interest. The great author's impact on science and science fiction has not ended with his death. In 2003 The Heinlein Prize, an award for practical accomplishments in commercial space activities, was established. The prize, initially worth $500,000, will be given to one or more individuals who have achieved practical accomplishments in the field of commercial space activities. Robert Heinlein was never conventional as a writer, engineer or human being, but maybe that's why his works as still so widely read and discussed. Throughout his life he refused to be pigeon-holed into a certain role in society: I am free, no matter what rules surround me. If I find them tolerable, I tolerate them; if I find them too obnoxious, I break them. I am free because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do.- Robert A. Heinlein Links to Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke

Copyright Lee Krystek 2007. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|