pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Notes from the Curator's Office:

The Nostalgic BBS For almost two decades, from the late 70's through the mid 90's, a subculture flourished throughout most of the United States and parts of Europe and Asia. It involved thousands of mostly young, technically-oriented people exploring the capabilities of the newly developed personal computer to allow communication and socialization in ways never seen before. I've heard the term "modeming" used for this activity, and it isn't a bad idiom as all the activity required the use of a phone-based modem that allowed two computers to talk. Perhaps a more appropriate adverb for this is "BBSing" though that particular combination of letters sounds rather awkward to me. In either case, the activity in question involved communicating via a BBS or Bulletin Board System. These kids (and many of them were just high-school and college students) were experimenting with primitive versions of applications that would pave the way for today's social networks, like Facebook and MySpace, peer-to-peer networks, line Napster and Bit Torrent, and online games like World of Warcraft and Guild Wars. The Personal Computer To understand the BBS movement you have to go back to the late 70's. The personal computer was just starting to appear in a number of different forms. The Apple II was perhaps the first of these that was actually able to run some useful applications. I owned an Atari 800, which had great graphics, but was a bit short on software. Radio Shack had a PC called the TRS-80 and Commodore fielded a machine known as the 64. Things really started moving in 1981, however, when IBM released their version of the PC. It quickly became an open standard by 1982 and cheap clones started appearing on the market. Soon, anybody who was really interested in owning a personal computer could afford it for a few thousand bucks.

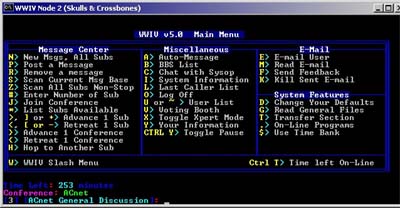

Remember, this was an era with no internet. No email. No instant messaging. No mobile phones. The fastest way to contact somebody was by a landline telephone , but a call across the country might cost you a $1 a minute (that was an uninflated dollar to boot). A letter was cheaper, but it could take over a week for the post office to deliver a coast-to-coast envelope. Overnight shipping companies didn't yet exist. The Computerized Bulletin Board System It was in this environment in 1979 that the first Bulletin Board System was developed by Ward Christensen, computer programmer for IBM. Christensen worked on mainframe computers during the day, but experimented with PCs at night. He, along with his partner, Randy Suess, called the software CBBS for "Computerized Bulletin Board System." He took the name from the community bulletin boards that you might see at a college or library where people could post and pick up messages. His software allowed people to do this electronically. To connect to CBBS and the other BBSs that would follow, you needed three things. First of all a computer. In those days it might be any of a number of units I mentioned above. Then you needed a device called a modem. This allowed the computer to talk over a regular telephone line to another computer. Finally, you needed a piece of software for the computer that took what was coming through the modem and put it up on the screen so you could see it. This was initially done with a program called XMODEM. A typical BBS of this era was run as a hobby. Initially this was done by people who had an interest in computers either because they were part of a computer club or because they were in the computer business. Anybody who was interested in becoming a "SysOp" (short for "System Operator") by turning his computer into a BBS needed not just the computer but a modem to take the calls and software like Christensen's CBBS. As the hobby spread, dozens of different BBS programs appeared inspired by Christensen's software. I was personally partial to boards that ran a program called WWIV written by Wayne Bell in 1984. WWIV was a popular BBS program because Bell not only released the program itself for people to use but also the source code necessary to make changes to the system and add new features. This early version of the Open Software movement allowed a lot of people to contribute to WWIV making it a better system.

Perhaps the most useful feature of the early BBSs was simple email. A user could dial into a BBS and leave a message for another user. Or he could post a message to a forum for everybody to read. Typically these forums would have particular topics. Given the technical orientation of many of the early users they were often about computers or software. And if not about techy stuff, the topics often involved science-fiction or fantasy. (Probably half the forums I saw were somehow linked to some aspect of Star Trek). Networking the BBS BBSs in the beginning were a localized phenomenon because the expense to make long calls outside your local telephone zone was prohibitive. However, in 1994 a computer enthusiast named Tom Jennings decided to connect a few computers running his Fido BBS software together so they could move messages between each other. This was the beginning of FidoNet. Eventually it would evolve into a network of over 20,000 BBSs (or nodes) around the world. When the internet eventually came into general use in the mid 90's, FidoNet also provided a way for these BBS's to connect to the worldwide web and exchange email. WWIV had its own network, WWIV net, which serviced mainly WWIV BBSs. Eventually both networks would not only move messages, but files so that a file placed on a BBS in Netcong, NJ, would automatically be distributed to all other members of the network, even as far away as Sydney, Australia. How did they do it? The BBS in Netcong wouldn't directly phone the BBS in Australia, but would forward the file to the next BBS on the network. Then the next BBS would forward the file on to the next on the network, and so on until the file finally reached its destination.

This sort of networking was slow, but very cost effective. It might take a few days for the message or file to work its way around the world, but it was still faster than sending a letter and certainly cheaper than posting a floppy disc containing a file through international mail. The cost wasn't even borne by the sender or receiver, but split up among the owners of the BBSs, who had to pay for the call between the boards. Often, however, they were able to re-coup some of the money through donations. Primitive Peer-To-Peer While FidoNet used a strict hierarchical arrangement to connect all the nodes, WWIVnet used a system that allowed the network to figure out which available route was the fastest for any particular message or file to move across the network. This arrangement was probably the first time a network had ever been set up like this and is very similar to the peer-to-peer network arrangements used today. Why would you want to send a file around the world? For many of the same reasons people patronize those peer-to-peer networks today. While high-res pictures and music were often too bulky to be sent across such slow dial-up networks, computer programs were smaller in those days and much software distribution was done this way. While the result of some of this was copyright infringement as people traded pirated programs, many of the programs moved around were shareware. Developers of shareware might give their programs way for free, requesting a donation if you used them and liked them. Others used it as a way of marketing their wares by giving you the basic program for free but charging a fee for a key that would unlock additional features, or in a game, new levels. Perhaps one of the most famous programs marketed through shareware distributed on these BBS networks was the game Doom. Although it wasn't the earliest of the "first-person shooter" games, it did much to popularize this type of entertainment. When the game was released in 1993, almost all of the 10 million people who had it installed on their computer over the next two years got their copy by logging on to a BBS.

Multiplayer Games While BBSs allowed games to be delivered electronically, they also served as gaming platforms themselves. The games were very early versions of the multiplayer games now popular on the internet. Because a typical BBS only had one modem (so that only one user could be online with it at a time) the games were not real-time, but were played out over a number of days with each player taking one turn a day. My favorite game played on a BBS was called "Global War." This was an electronic version of the popular board game "Risk." It required 3 to 6 players. Risk was a particularly good game to adapt to run on a BBS because each of the players turns is long and requires little participation of the other people in the game except to roll their dice in response to an attack. Since no dice were used in the electronic version (the computer used a random number generator routine instead) the defending player did not actually need to be online at the same time as the attacking player. A game of Global War might take four to five days to complete, with each player getting one turn a day. Because the games moved so slowl,y many players compensated by being involved in multiple games at the same time. Another popular game found on most BBSs was "Trade Wars." This game took place in a future world where interplanetary travel was possible. The object was to make money by trading various commodities between space stations and planets. For this you needed a spaceship (I named mine the Century Eagle as a parody of the Millennium Falcon). You could purchase this at a shipyard, then as you became richer you could trade up to a faster, better-armored vessel, or equip the one you had with better weapons. Other players on the BBS would compete with you, and if weren't careful, blow your ship to smithereens.

ANSI Art Trade Wars paved the way for a lot of multi-player games that followed over the years; however, nobody who has seen a modern multi-player networked game would be impressed with the graphics. Because the communications speeds involved were so slow, images sent across the lines couldn't be pixel based. Even with a fairly swift 2400 baud modem that would send around 240 characters across the telephone line per second, a low resolution 640x 480 pixel image might take five minutes to download. Instead, a method called character graphics was employed. In this arrangement the screen was divided into a grid usually 80 characters wide and 24 characters high. This meant that the whole screen could be expressed in only 1920 characters and it would take less than 8 seconds to download with a 2400 baud modem. The problem with this arrangement, however, was that only whatever 128 characters that were in the character set could be shown on the screen. Of these 128 half were taken up by numbers, upper and lower case letters, and special characters. The rest, however, could be used for things like boxes and lines that might be used to make graphic screens. These used in conjunction with a set of codes standardized by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) that controlled things like position and color, allowed for a surprising amount of flexibility from what seemed like a limited system. It was possible to travel to a space station in Trade Wars, and actually see a primitively animated film in the station's movie theater. In addition to the ANIS art in games, there soon developed whole art groups organized across BBSs. They would create their artwork in ANIS and then share them as "packs" of files across the network. A SysOp would often individualize his BBS by having a fancy ANSI art screen scroll up when you logged on to his system. Though most BBSs were operated by individuals for the love of it, a few made the jump to commercial sites. The most successful of these were BBSs that supported an existing company or service. If you bought the new XYZ sound card for your PC, you could download the newest drivers from the XYZ company board.

Others managed to collect money from members for providing the BBS service by offering multiple simultaneous access and extensive forums and files. Most of these services found it was hard to compete with the free access offered by private enthusiasts, however. End of an Era As the internet became more and more available to people in the mid 90's, interest in BBSs waned. Many closed up shop. Others became websites. A few of the large commercial ones turned into internet dialup ISPs. A few boards continue to exist, though most of these can only be accessed via the internet rather than dial up modem. The era off BBSing disappeared almost as quickly as it had appeared. Parts of it still remain serving people in surprising ways. FidoNet still exists and in some countries where the internet is censored, it provides a way to communicate without the government watching. They can easily monitor a few internet trunks, but it is much harder to regulate thousands of dialup phone lines. For those who want to know more about this era, you may want to check out BBS: The Documentary at http://www.bbsdocumentary.com/. Producer Jason Scott, a historian of this movement, explores the phenomenon and the people who made it happen. Copyright Lee Krystek 2012. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|