pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

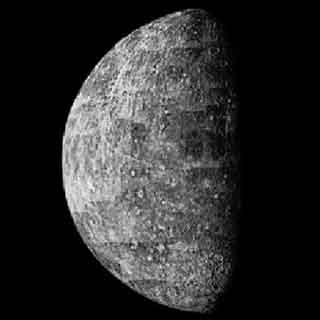

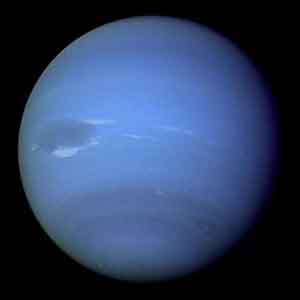

The X-Planets Throughout the centuries astronomers have searched for new planets, often without success. Is there a 10th planet in our solar system still waiting to be found, or is looking for it simply a wild goose chase? On December 22, 1859, Urbain LeVerrier, of the Paris Observatory, opened a letter from a man named Lescarbault. As he read it, he felt a rush of excitement come over him. Lescarbault was a country doctor and amateur astronomer. According to the letter, on March 26th of that year, Lescarbault had observed a round black spot moving across the face of the sun in an upward-slanting path for one hour and a quarter. LeVerrier put the letter down. If what the doctor said was true, it might prove one of LeVerrier's predictions: that there was an unknown planet in the solar system. A planet that circled within the orbit of Mercury, which was then the closet known planet to the sun. This was not the first time LeVerrier had predicted the existence of an unknown planet. In 1781 the German-British astronomer William Heschel spotted a star that seemed to move from night to night. He soon realized it was a new planet, the first discovered since ancient times. The planet, which was located beyond Saturn, was given the classical name Uranus. In 1846 LeVerrier had noticed irregularities in the movement of Uranus and predicted that there must be another unknown planet beyond Uranus causing the disruption. LeVerrier was able to predict the location of the planet and it was then spotted in the sky by the German astronomers Johann Galle and Heinrich d'Arrest.

LeVerrier, not one to avoid publicity, suggested that Uranus be renamed for Heschel, the finder, and the new planet be named for himself. Unfortunately for LeVerrier, a British mathematician named John Couch Adams had actually predicted the location of the planet almost a year earlier than LeVerrier. The two men wound up sharing the credit (Adams would have gotten full credit for the prediction except he couldn't convince any British astronomers to take the time to turn their telescopes to look for it - see sidebar) The planet, rather than being named LeVerrier, was given the name of the Roman God Neptune. Vulcan LeVerrier badly wanted sole credit for discovering a planet so he turned his eyes toward the other end of the solar system. He noticed that the planet Mercury also had irregularities in its orbit. This led LeVerrier to predict there would be found a small planet closer to the sun than Mercury. The observation by Lescarbault might be the proof of his prediction. After finding a colleague to go with him as a witness, LeVerrier set out immediately to the village of Orgeres where Lescarbault resided. Without identifying himself, LeVerrier rudely confronted the doctor, demanding to know how Lescarbault came to the absurd conclusion that he had observed "an intra-Mercurial planet." Lescarbault recounted the story in detail. LeVerrier, now convinced of the doctor's tale, revealed who he was and congratulated the somewhat bewildered physician. Returning to Paris, LeVerrier saw to it that the doctor was awarded the Legion of Honor.

The astronomical world was soon filled with excited discussion about LeVerrier's new planet. He calculated the size of the planet to be one-seventh that of Mercury. The new planet he figured would transit the sun every April and October. LeVerrier, deciding to avoid the controversy he had with Neptune, suggested that the new planet should be named Vulcan. Astronomers all over the world began to watch for Vulcan during the period it should have been visible according to LeVerrier's calculations. They were usually disappointed. With the exception of some erroneous observations (which usually turned out to be sunspots) Vulcan was never seen. By the end of the 19th century most rational astronomers no longer believed in the planet and in the early 20th century Einstein's General Theory of Relativity explained how the curvature of space-time would cause the irregularity of Mercury's orbit. With that, LeVerrier's planet Vulcan disappeared. Planet-X Shortly after the discovery of Neptune, astronomers began to conjecture that there must be another planet farther out. Neptune did not fully explain the disturbances in the orbit of Uranus, and Neptune itself seemed to have an irregular orbit. A number of mathematicians and astronomers tried to predict the location of this planet and find it, but without success. Perhaps the most persistent of these searchers was a man named Percival Lowell. Percival Lowell was born into a wealthy Boston family in 1855. He built his own fortune, then took an interest in astronomy after reading Camille Flammarion's book, La Plančte Mars, in 1893. Mars would be coming into opposition (its closet approach) with the Earth in 1894 and Lowell decided to fund an expedition to Arizona for the purpose of observing it in the clear, dark western skies. Lowell paid to build a private observatory which was constructed near Flagstaff, Arizona. Lowell was a brilliant man, but he often let his imagination run wild. In 1877 the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli discovered what looked like a series of "channels" across the face of Mars. This was improperly translated as "canals" in English, a word which carried with it the suggestion of intelligent design and construction. Lowell built upon this "canal" theory and said he had observed changes along the surface of Mars that seemed to relate to the growing seasons and perhaps farms. In his own words:

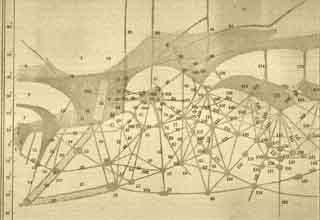

Speculation has been singularly fruitful as to what these markings on our next to nearest neighbor in space may mean. Each astronomer holds a different pet theory on the subject, and pooh-poohs those of all the others. Nevertheless, the most self-evident explanation from the markings themselves is probably the true one; namely, that in them we are looking upon the result of the work of some sort of intelligent beings. . . Later observations by others showed no canals on Mars and we now know there is no intelligent life on the planet. It has never been clear what exactly Lowell, Schiaparelli and others observed, but it may have been optical illusions introduced by their telescopes. In addition to his interest in Mars, Lowell was also determined to discover the hypothetical planet past Neptune and coined the term "Planet-X" to describe his quarry. He conducted two searches for the planet, one ending in 1909 and the other in 1915, without success. Lowell died in 1916 and his failure to find Planet-X was the biggest disappointment of his life. In 1929 an amateur astronomer, Clyde Tombaugh from Kansas, was hired by the Lowell observatory to continue the search.

Almost a year after he had started his work, Tombaugh examined some photos he'd taken a few days apart in January of 1931. When Tombaugh compared the two, which were of the same section of the sky, he noticed one of the "stars" had moved. Since stars do not move relative to the rest of the stars in the sky, the object must really have been an asteroid, comet, or new planet. Further observations confirmed that the object appeared to be a planet beyond Neptune. It was given the name Pluto. Lowell's Planet-X had been found. Or had it been? Predictions said that in order to explain the kind of disturbances in the orbits of Neptune and Uranus, Planet-X would have to be more than six times the mass of Earth. Observations now show that Pluto, along with its tiny moon Charon, have only about one four hundredths the mass of Earth. Some scientists now argue that Pluto doesn't even deserve the status of a planet, but instead should just be considered the largest object in a swath of billions of comets called the Kuiper Belt that surround the orbit of Neptune. Tombaurgh continued his search for another Planet-X for 13 years without success and decided that no tenth planet was out there. "I observed seventy percent of the entire sky and would have found it if it existed," he said.

Some scientists agree, arguing that the perceived irregularities in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune are the result of observational errors made by early astronomers who didn't have access to cameras and had to sketch the position of the planets by hand. Other aren't so sure. Many astronomers seem to agree that there is still a possibility that there are several Pluto-sized planets moving in orbits around or beyond Neptune. Fewer think that a planet about the size of Earth, or larger, may still be hiding in the skies. Those that do think a large planet may be out there think it may follow a highly-elliptical orbit that takes it far past Pluto, or that it is currently located in the southern sky in a very dense portion of the Milky Way where it would be difficult to spot. Nemesis It there the possibility that there is a Jupiter-like planet or something even larger in orbit around our Sun at a distance many times that of Pluto? Scientists had long noticed that every 26 million years or so there seemed to be a mass extinction of life on earth. In 1984, Daniel P. Whitmire and John J. Matese of the University of Southern Louisiana developed a theory that this was caused by a low mass companion star of the sun, which they called Nemesis (after the Greek God of vengeance). According to their theory, Nemesis (following an elliptical orbit) plows through a belt of billions of comets called the Oort cloud every 26 million years sending swarms of them sunward. Some of them hit the Earth, causing the extinctions. It is not at all strange that the sun might be part of a binary star system. Most stars seem to form in pairs. However, in order for the existence of this second star not to be obvious to us because of its light, it would have to be a very dim type of star (called a red dwarf) or a dark type of star, known as a brown dwarf. According to the theory it would also be very far away, perhaps as far as 3 light years.

Another possibility suggested by Whitmire is that Nemesis is not a star at all, but a planet. Another Planet-X, so to speak. If this were the case it might be about the size of two to five earths and orbit the sun at perhaps three times the distance of Pluto. In this version of the theory the planet would pass through the Kuiper Belt of comets every 26 million years, sending some of them earthward. While some astronomers continue to search for Nemesis, or the new Planet-X, most are skeptical of its existence, pointing out that the 26 million extinction cycle may not be as regular as was once thought. Varuna and Beyond There are certainly more worlds to find in space. On November 28, 2000, astronomers discovered a new member of the solar system in the Kuipter Belt. It was subsequently named Varuna. Although Varuna was smaller than Pluto (it is only 550 miles wide compared to Pluto's 1,440) and not considered a planet, it did demonstrate that there may be other undiscovered objects at the edge of our solar system. Then in January of 2005 astronomers using the Palomar Observatory in California, found a body in space orbit in the sun at a distance of 10 billion miles - 3 times farther away than Pluto. The object, which was slightly larger than Pluto and has a small moon, was been designated UB313 (Later given the name Eris). It's finders originally called it the 10th planet, but officially it has been designated a "Dwarf Planet" along with Varuna and Pluto. Ironically finding a "10th planet" didn't increase the number of planets at all, but caused the demotion of poor Pluto so that now our solar system only officially has eight. Astronomers continue to search the skies for additional members of the solar system, and there are hints that Eris is not the only body out there. Even if we find no more major planets in our solar system, however, there are still planets in the skies.

In the fall of 1991 astronomer Alex Wolszczan of Cornell University was studying a type of star called a pulsar when he noticed something unusual. Some pulsars normally spin at over a hundred rotations per second and each time they turn send a strong radio "pulse" out into space. The spin of such a pulsar never varies, making the bursts of radio incredibly regular. Wolszczan was amazed to find that this particular pulsar, designated PSR 1257+12, changed the timing of its pulses over time. Sometimes the pulses came late, sometimes early. Wolszczan realized that the only explanation was that the star was wobbling due to the pull of the gravity of several planets in orbit around it. Since then many more planets have been discovered outside our solar system and there are probably billions more to find. Although because of the huge distances involved astronomers have to infer their existence by observing their effects on their star rather than seeing them in a telescope, scientists are confident they are there and have even been able to make some predictions about their size and climate based their gravitational effects. In the future NASA is hopeful the a super space based super-telescope may be put into actions to that we can directly observe these distant bodies and gain more information on what the are like. One thing is sure, now that we are looking beyond our own solar system, there will never be a shortage of "Planet-X's" for astronomers to search for. Copyright 2000-2007 Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|