pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Mystery of the Rosetta Stone - Part 2:

The Race to Decipher the Code Jacques-Joseph Champollion was working in his office at the Institute of France on September 14 of 1822 and worrying about his little brother. The younger Champollion, Jean-Francios, had been working night and day on his obsession: deciphering the strange little drawings (known as hieroglyphics) left by the ancient Egyptians. Suddenly the elder Champollion's door burst open and Jean-Francios rushed in and in a frenzy shouted, "I've done it! I've done it!" He started to tell his brother what he had done, but before he got very far he fell to the floor as if he were dead... When the scientists that accompanied Napoleon to Egypt in 1798 returned to France, they started publishing their findings. In 1802, Vivant Denon's illustrated book, Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte, came out featuring his sketches of Egyptian ruins. It was a huge bestseller in France and throughout Western Europe. This, and the reports from other scholars, set off a wave of Egyptomania throughout the country. Egyptian styles found their way into architecture, ornaments and fashions. Napoleon actively promoted Egyptian motifs as a method of breaking away from the symbols used by previous regimes. This mania added even more attention to the mystery of the Egyptian's strange, unreadable text, hieroglyphics, and scholars soon realized that solving the riddle of understanding this script would be a way to fame and fortune. Soon the race to decode the text was on. Although the Rosetta Stone, which was covered with a version of a proclamation in both Egyptian and Greek, became property of the British, the French scientists had made multiple copies of the text of the stone while it was in their possession by rolling ink over the surface of the slab and pressing paper against it. This produced a clear negative image of the writing. Once the British got a hold of the stone they did the same thing along with also making plaster casts of it that were sent to the universities at Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Trinity Colleges. Soon scholars all over Europe were trying to use the copies from the stone to figure out the meaning of the Egyptian scripts. Most of the researchers focused on the second portion of the stone containing the Eygptian"demotic" script. It was thought that since this type of Egyptian lettering was cursive (that is, the letters were connected) this script must use alphabetic symbols, like most western languages, instead of the picture symbols of the hieroglyphics. Once the scientists could determine the alphabet, they thought, the words should be easy to decode. In 1802, one French scholar, Sylvestre de Sacy, started looking at the proper names in the Greek and tried to match them up with the names in the demotic. He did manage to find the names, but could not determine which markings were the individual letters. Eventually he gave up saying, "The problem is too complicated - scientifically insoluble!" A Swede, Johan Akerblad, who was a student of Sacy, made better progress. He was able to find in the demotic all the proper names mentioned in the Greek portion of the passage and from that created an alphabet composed of 29 letters. He was also able to demonstrate that these letters occurred in other words in the passage that weren't proper names. There his progress stopped, however. Later on it was found that Akerblald's demotic alphabet was about fifty percent correct. Thomas Young

Much more progress was made by the British Dr. Thomas Young. Young, born in 1773, had a gift for languages from an early age. He read by the age of two and by twenty knew Arabic, Persian and Turkish along with several other languages. Fortunately an inheritance that was left to him allowed him to pursue any subject of study that interested him. As it turned out, this included medicine and physics. He even wrote a book called The Undulatory Theory of Light. In 1804 Young got a hold of one of the copies of the stone and decided to take a crack at decoding the unknown scripts. Young, like everyone else, started with the demotic. He studied the names in the Greek and compared them to the symbols in the demotic that Akerbald had identified as names. He noticed that each time the names appeared, they were set off on either end by characters that looked a lot like parentheses. It occurred to him that this was very similar to the names found in the oblong hieroglyphic cartouches. Could this be a simpler version of the cartouche? Young was able to go on to identify groups of letters that composed words in the demotic, but after that he was stymied. Instead of giving up, however, he decided to try working on the hieroglyphic section. It was a good decision. He soon came to recognize that for every demotic symbol, there was a hieroglyphic one. In fact, the demotic symbols were just simpler versions of the hieroglyphical ones. This was a major breakthough. The demotic script was apparently just an easier to write version of hieroglyphics in the same way that cursive writing is an easier, less formal way of writing printed English. Young also came to believe that in some of the non-Egyptian names in the passage the letters didn't stand for an idea, but for phonetic sounds, just like in English. He was right, but still could not decode the rest of the demotic or hieroglyphic text. What he had learned, however, Young put into an article for the Supplement to the 14th Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica published in 1819. Jean-Francois Champollion

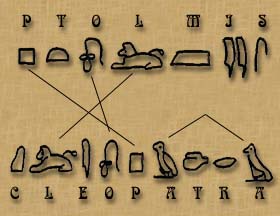

The French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion was not independently wealthy, like Young, but he did possess a similar natural gift for languages. Born in 1790, he decided and early in his education to make his life goal to research the origins of mankind. To do this he thought it would be necessary to learn and understand as many of the Middle Eastern languages as he could. Jean-Francois had an older brother, Jacques-Joseph, who recognized the genius in his sibling and did everything he could to furnish him with an education that would allow him to flourish as a scholar. To this end he took him to live with him in the city of Grenoble. While there, the younger Champollion, at age eleven, was invited to visit the house of Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Fourier. Fourier was a famous scientist and had been one of the scholars that had gone to Egypt with Napoleon. Fourier was also connected with the school Champollion was attending and had heard good things about the young genius. At first Champollion was so overwhelmed by being able to meet Fourier - (who was the most powerful person in Grenoble) - he could hardly speak. As Fourier began to tell him about the Egyptian expedition and about the Rosetta Stone with the strange symbols that nobody could read, Champollion became fascinated. Fourier, had a copy of the stone's text among his Egyptian collection and showed it to the boy. Champollion left the meeting having decided he would not only study hieroglyphics, but determined to be the person who would finally decipher their meaning. To this end Champollion had learned Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Sanskrit and Persian along with several western languages by the age of 17. The language he really thought would unlock the key to the stone, though, was Coptic. Champollion suspected that the Coptic language, once used by Egyptian Christians, might have elements of the ancient hieroglyphics preserved within it. Like earlier scholars, Champollion at first thought that the hieroglyphs were completely symbolic. Around 1822, however, he reversed his thinking and pursued the idea that at least some of the symbols were phonetic in nature. Critics of Champollion argue that he got the idea from reading Young's article in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, but Champollion later denied this. To go beyond Young's work Champollion would have to show that other names in the hieroglyphic script were written using phonic symbols. The number of names on the Rosetta Stone itself was limited, so Champollion would have to search for other texts that might fulfill his requirements. This turned out to be a frustrating task, but fortunately a colleague sent him an inscription he'd seen in the ruins of a temple on the Nile River island of Philae. Like the Rosetta Stone this inscription was written in both Greek and hieroglyphics and contained the names of Pharaoh Ptolemy VII and his Queen, Cleopatra II. Correcting some of the mistakes made by Young he was able to show that many of the hieroglyphic symbols in the name Ptolemy were in the right place in the name Cleopatra if those symbols carried phonetic values. The Breakthrough

Over the next several months Champollion was able to decode more than eighty names and identified the meanings of more than one-hundred hieroglyphic symbols. Still, he couldn't be sure that the hieroglyphics were purely phonetic. He had mostly decoded names from the period when the Greeks were ruling Egypt. Suppose their names were special cases because they were foreign? To test this idea, he obtained some inscriptions from an earlier period and examined the royal names found in the oblong cartouches. He recognized one as having a double "s" sound on the end. The symbol in the beginning appeared to be that of the sun, something he knew from his studies of Coptic to be pronounced "rah." The symbol in the center seemed to be connected with the word "birthday" on the Greek translation of the Rosetta Stone. He decided to use the Coptic word meaning "to give birth" which was pronounced "mes." When he put it all together he got the name Rameses (meaning "The Child of the Sun God"). Rameses, Champollion knew, was one of the most famous pharaohs mentioned in the Bible. Champollion used the same approach to decode another name and realized the significance of what it meant: hieroglyphics were not strictly symbolic or phonetic, but a mixture of both. This was the breakthrough that sent him running to his brother's office to give him with so much excitement that he fainted upon arriving. Over the next months he continued to use his knowledge of Coptic to build up a set of translated hieroglyphics and rules for reading the script which he published in a book in 1824. In this book he explained that the key to understanding the writing was that it was "symbolic and phonetic in the same text, the same phrase, and the same word." His success made Champollion instantly famous. He got to meet the King of France, Louis XVIII, and in 1826 was put in charge of the Egyptian Museum at the Louvre. Finally, in 1828 he was able to travel to Egypt itself to journey up the Nile River and read the inscriptions on the ancient temple ruins for himself. He continued to work on compiling a dictionary of hieroglyphics and associated grammar until his death in 1832 at the age of 42. Since then archeologists have been able to expand Champollion's rules and use them to translate thousands and thousands of lines of hieroglyphic text, opening up the ancient Egyptian history to our understanding. Meanwhile, the strange slab of rock that started it all when it was found at Rosetta still sits at the British Museum in London where it is viewed by thousands of visitors each year. Compared to the statues around it, it may look unimportant, but more than the impressive art that surrounds it, it was the key to understanding the Egyptian civilization. A Partial Bibliography The Riddle of the Rosetta Stone by James Cross Giblin, Harper Collins Publishers, 1990. The British Museum Book of The Rosetta Stone by Carol Andrews, Peter Bedrick Books, 1981. The Keys to Egypt by Lesley and Roy Adkins, Harper Collins Publishers, 2000. The Mystery of the Hieroglyphs by Carol Donoughue, Oxford University Press, 1999. Copyright Lee Krystek 2006. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|