Surprising

Science:

Who

is the Father of Television?

|

In

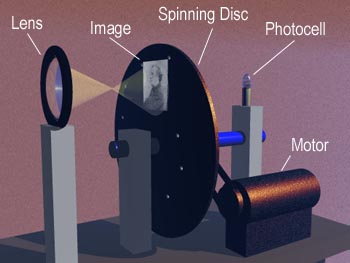

this picture of Baird's Televisior the housing for

the spinning disc can clearly be seen. The picture appeared

on the small screen at the right. (Courtesy

Early

Television Foundation)

|

Ever hear of Vladimir K. Zworykin? How about John

Logie Baird? Or maybe you know the name of Paul Nipkow? If not,

how about Charles Francis Jenkins? No? Well surely you have

heard of Philo T. Farnsworth!

Who are these people? They all have a claim to

the title of "The Father of Television." Which one,

if any, is the rightful owner to that moniker, however?

The creation of television, one of the most important

inventions of the 20th century, has it roots firmly planted

in the 19th century. It was the logical outgrowth of the technology

of the telegraph and the photograph. As early as the 19th century,

inventors were filing patents on the devices that allowed for

transmission of moving images over wire.

Almost all technologies that display moving pictures

depend on a phenomena called persistance-of-vision. If the human

eye is presented with a series of still pictures very quickly,

faster than about 10 a second, it sees them not as individual

pictures but one continuous image. A motion picture camera uses

a long strip of film to take image after image of a scene, capturing

any movement within the series of pictures. As these are played

back through a projector, it gives the viewer the illusion of

a continuous moving scene.

Inventors wishing to transmit a moving picture

electrically would have to find a way to do something similar

by capturing image after image and sending them down a wire

to be reconstructed for viewing at another location.

Mechanical

Television

A German, Dr. Paul Nipkow, built the first, crude

machine to do this in 1884. Nipkow's camera device was based

on a spinning disc with 24 small holes punched in it. The holes

were arranged in a spiral so that as the disc was spun they

would one-by-one sweep out area where an image was focused onto

the disc with a lens. On the other side of the disc was a light-sensitive

photo cell that would generate an electrical signal when it

was struck by the light coming through the holes. In this way

the image was turned into an electrical signal. Every time the

disc rotated one full turn, another image would be sent down

the wire.

|

How

a mechanical TV works: The lens focuses the image on

a spinning disc. Holes sweep by the image allowing one

small point of light to pass through to a photocell

at a time. The photocell changes the varying light to

an electrical signal which is sent on a receiver which

reconstructs the image.(Copyright

Lee Krystek, 2002)

|

Nipkow's receiver worked in reverse of his camera.

Instead of a photo cell there was a neon lamp. The neon lamp's

brilliance varied depending on the signal coming from the camera

and the light would pass through another spinning disc, synchronized

to the first, so that on the other side of the disc a fuzzy

image would form.

There were many problems with Nipkow's invention

and it never made it out of the laboratory: For one thing the

neon bulb did not generate enough light to make a very usable

picture. When a brighter bulb became available in 1917, other

inventors began to have an interest in Nipkow's work. In America

Charles Francis Jenkins started to build a system using a variation

of the spinning discs designed by Nipkow. In England an inventor

named John Logie Baird started experimenting with a similar

system.

Baird was 34 years old when he started building

his "Televisor" system. Working on a shoestring budget,

he built his first device using objects found in the attic where

he was experimenting. An old tea chest was used to support the

electric motor that turned the discs. The discs themselves were

cut out of cardboard. Other parts were mounted upon pieces of

scrap lumber. His lens came from an old bicycle lamp. Glue,

sealing wax and wire held the device together.

Amazingly, the jury-rigged system was able to produce

a tiny, flicking image. In 1926 Baird demonstrated a more refined

version of his mechanical television system to members of Britain's

Royal Institute. This lead to news coverage in the London

Times and money from financial backers so he could perfect

his device. By 1930 Baird was transmitting images over the BBC

transmitters at night after normal radio programs had ended.

This became the world's first regular television service.

Despite the success of Baird, this form of television,

which was referred to as mechanical television because of the

turning motors and discs involved, had many technical limitations.

Engineers working on mechanical televisions could not get more

that about 240 lines of resolution which meant the images would

always be somewhat fuzzy. The use of a spinning disc would also

limit the number of new pictures per second that could be seen

and this resulted in excessive flickering. It became apparent

that if the mechanical portion of television could be done away

with, higher quality and steadier images might be the result.

Electronic

Television

The first man to envision an electronic television

system was a British electrical engineer named A. Cambell Swinton.

In a speech he gave in 1911, Swinton described a design using

cathode-ray tubes to both capture the light and display an image.

A cathode-ray tube was a glass bottle with a long neck on one

end and a flattened screen on the other. The bottle was pumped

clear of air so that an "electron gun" in the neck

could shoot a stream of electrons toward the flattened end of

the tube which was covered with a coating of phosphor material.

When the electrons hit the material it would glow. By sweeping

the electron stream back and forth in rows from top to bottom

and varying the intensity of the stream, Swinton reasoned, an

image could be drawn in the same manner that Nipkow's disks

did.

A modified version of the tube could also be used

as a camera. If the flattened end could be given a sandwich

of metal, a non-conducting material and a photoelectric material,

light focused on the flattened end with a lens would produce

a positive charge on the inside of the surface. By sweeping

the electron stream across the flattened end, again in rows,

the charges could be read and the image could be turned into

a signal that could be sent to the display screen to be seen.

Swinton's idea almost exactly describes the way

modern electronic television works. While his forevision was

near perfect, Swinton, nor anyone else at the time, knew how

to actually engineer such a system and make it work. An electronic

system, if it could be made to work, however, would operate

at much faster speeds than any mechanical system could and would

allow the picture to be composed of more rows, therefore increasing

the quality of the image.

|

Philo

T. Farnsworth.

|

It was eleven years after Swinton's lecture that

a teenager from Utah became interested in electronic television.

Philo T. Farnsworth had read about Nipkow's disc system and

decided it would never produce a high quality picture. After

experimenting with electricity, he declared to one of his high

school teachers that he thought he could devise a better system.

He proceeded to lay it out for the surprised man on the classroom

blackboard. The teacher encouraged Farnsworth and Farnsworth

set out to California to build a laboratory where he could experiment

with his ideas. Working in darkened rooms in Los Angeles and

later San Francisco, Farnsworth kept his work so secret that

his laboratory was once the subject of a raid by police, who

thought that he was using a still to produce illegal alcoholic

beverages.

By September of 1927 Farnsworth was transmitting

a sixty line picture from camera to screen using an entirely

electronic system. It was at this point in time his work drew

the attention of David Sarnoff. Sarnoff was chief of the Radio

Corporation of America (RCA): the leader in supplying radios

and radio parts to the United States.

Many of RCA's radio patents would soon expire, so

Sarnoff was searching for another market he could corner and

television was the obvious choice. After hiring Vladimir Zworykin,

a Russian immigrant who had been experimenting with mechanical

television for a decade, Sarnoff sent him to California to look

at Farnsworth's work. Later Sarnoff would visit Farnsworth's

laboratory himself.

Sarnoff and Zworykin quickly realized the value

of Farnsworth's invention and Sarnoff tried to buy the young

man out for $100,000. Farnsworth, thinking he could make more

in collecting patent royalties from RCA than selling his invention

to them, refused. Sarnoff, miffed, said, "Then there's

nothing here we'll need" and sent Zworykin off to build

their own version of the technology.

Farnsworth's designs kept showing up in Zworykin's

work and lawsuits between the two companies followed. Eventually

RCA was forced to pay Farnsworth $1,000,000 in licensing fees,

but the onset of WW II delayed the introduction of television

to most of the United States and the market for electronic television

did not really take off until after the war. By then many of

Farnsworth's key patents had expired and he never made the money

he probably really deserved for his contributions to electronic

television.

Adding insult to injury, most of the history of

television was written by RCA employees and they, perhaps in

revenge for the license they were forced to take out, left Farnsworth's

contributions completely out of the story.

Demise

of Mechanical Television

So what happened to the mechanical television being

broadcast in Britain? Baird soon realized he needed to get the

help of the BBC to make his mechanical system a complete success.

By the 1930's, however, the BBC realized that the future was

with electronic TV, not mechanical. Starting in November of

1936, Baird's mechanical system was broadcast on alternating

weeks with an electronic system from EMI. The British public

was invited to choose which one they liked best. The electronic

system was clearly superior and Baird was taken off the air.

Though Baird would try to sell his system to movie houses, those

plans ground to a halt when WW II started and the BBC's TV service

was shut down until hostilities were over.

In 1939 RCA and Zworykin decided to demonstrate

their new electronic TV system at the World's Fair in New York

City. Not much more development was done until after the WW

II was over, but by 1946 people could buy a ten-inch table model

for $375.

So who was the true Father of Television? This ubiquitous

invention, like many others, had many people contributing to

its creation. It's obvious, however, that much of the credit

for making electronic television should probably go to Philo

Farnsworth. Court after court hearing Farnsworth v. Zworykin

acknowledge that his ideas found their way into the first commercial

systems built by RCA. Many of the processes that operate inside

a TV today were developed in his darkened, secret lab in California.

A

Partial Bibliography

They

All Laughed by Ira Flatow, HarperCollins Publishers, 1992.

Inventing

Modern America by

David E. Brown,

The MIT Press, 2002.

The

Scientific Breakthrough by Ronald W. Clark, G.P. Putnam's

Sons, 1974.

Copyright Lee Krystek 2002. All

Rights Reserved.