The Weekly

World News before it ceased publication was one of

the few newspapers still reporting hoax stories (Fair

Use).

|

Hoax Journalism

They scream at you from the magazine racks near

the checkout counter with improbable headlines like Aliens

Stole My Dog! Most people ignore them, or laugh at them.

As strange as it seems, however, these tabloids go back to long

standing-tradition in American culture involving authors as noteworthy

as Benjamin Franklin, Mark Twain and Edgar Allen Poe.

On August 27, 2007, one of the few remaining pillars

of a long-established American journalist tradition closed its

doors: The Weekly World News ceased paper publication.

Over the years the tabloid news magazine had featured such headlines

as:

Hillary

Clinton Adopts Alien Baby

Bat

Child Found in Cave

Mermaid

Caught in South Pacific.

The Weekly World News and its sister publication

The Sun often printed bizarre articles that either exaggerated

facts or were completely fabricated. Many people bought the publications

just for the humor within their pages. What most readers didn't

know was that such outrageously false news stories are hardly

a recent invention. The truth is that these newspapers are perhaps

the final holdout of a genre of fiction that has almost completely

vanished from the American scene: hoax journalism.

Hoax journalism has been around as long as there

have been newspapers, but perhaps it reached its zenith of popularity

in the 19th century. Many of these stories were not just exaggerations

of fact, or sloppy reporting. Some of the most well-known were

complete fabrications from beginning to end. Amazingly in this

era, newspapers from the smallest weekly publications to the biggest

daily city press printed hoaxes. Also, some of the most famous

names in American literature were behind the stories.

|

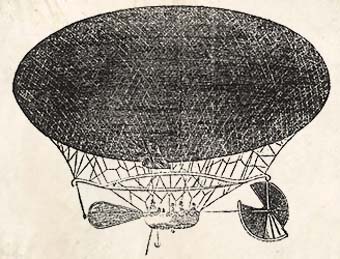

The

New York Sun included this illustration of the ballon

with Poe's article.

|

Mark Twain, the author of such classic American

books as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The

Adventures of Huckleberry Fin, started his career with

the fake story about an insane man in Carson City, Nevada, who

killed his wife and then went running through the streets of the

town "with his throat cut from ear to ear" while he carried his

wife's still warm scalp with him.

The

Great Balloon Hoax

Edgar Allen Poe, celebrated author of such stories

as The Tell-Tale Heart and The Masque of the Red Death,

wrote an article in 1844 which came to be known as The

Balloon Hoax. It was published in the New York Sun

and described the successful crossing of the Atlantic Ocean via

a balloon. In the article Poe described the construction of the

balloon (flown by a Mr. Monck, who was actually a well-know aviator

of that time) in perfect technical detail:

Like Sir George Cayley's balloon, his own was

an ellipsoid. Its length was thirteen feet six inches - height,

six feet eight inches. It contained about three hundred and twenty

cubic feet of gas, which, if pure hydrogen, would support twenty-one

pounds upon its first inflation, before the gas has time to deteriorate

or escape. The weight of the whole machine and apparatus was seventeen

pounds - leaving about four pounds to spare. Beneath the centre

of the balloon, was a frame of light wood, about nine feet long,

and rigged on to the balloon itself with a network in the customary

manner. From this framework was suspended a wicker basket or car.

|

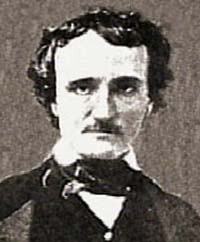

Edgar

Allen Poe wrote on of the most well-known hoaxes of the

19th century.

|

In truth, the actual crossing of the Atlantic by

a non-powered balloon wouldn't be accomplished for another hundred

years. Why did Poe participate in this fraudulent story? Though

he was recognized by some as an artist genius, Poe was low on

money. He had just moved his family to New York from Philadelphia

and had less than five dollars in his pocket. We he arrived he

aw a chance to cash in on an ongoing competition between the New

York Sun, Herald and Tribune newspapers. Each

wanted to be the first to break a sensational story and scoop

the other, even if it meant not bothering to check the facts.

Poe sold the story, then stood back and watched the excitement

it created. Later he wrote:

On the morning of its announcement, the whole

square surrounding the 'Sun' building was literally besieged,

blocked up-ingress and egress being alike impossible, from a period

soon after sunrise until about two o'clock P.M.... I never witnessed

more intense excitement to get possession of a newspaper. As soon

as the few first copies made their way into the streets, they

were bought up, at almost any price, from the news-boys, who made

a profitable speculation beyond doubt. I saw a half-dollar given,

in one instance, for a single paper, and a shilling was a frequent

price. I tried, in vain, during the whole day, to get possession

of a copy.

When the story could not be confirmed, the Sun was

forced to retract the article the next day, but not before it

had sold a lot of newspapers.

|

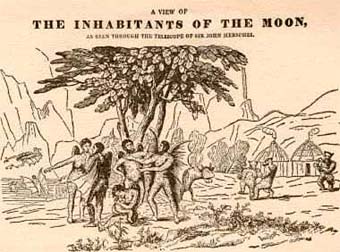

Illustrations

from the 1835 article offered to show readers what life

was like on the moon.

|

The

Great Moon Hoax

Perhaps the most famous journalistic hoax of the

era occurred a few years earlier in late August of 1835. The New

York Sun ran a series of articles supposedly reprinted from

the fictitious Edinburgh Journal of Science. In these an

Andrew Grant reported that Sir John Herschel, using a new, powerful

telescope, had discovered life on the moon. The articles described

a lunar landscape that included beaches, jungles and oceans and

was populated by bison, blue unicorns and tail-less, bipedal,

intelligent beavers. Perhaps the most startling discovery, according

to stories, was the existence of furry, winged, "moon men:"

Certainly they were like human beings, for their

wings had now disappeared and their attitude in walking was both

erect and dignified. They averaged four feet in height, were covered,

except on the face with short and glossy copper-colored hair,

and had wings composed of a thin membrane, without hair...

While Herschel was a well-known astronomer at the

time, there was no Andrew Grant and the actual author is believed

to be a Sun reporter named Richard Adams Locke. While this

series of articles seems outrageous today, many people at the

time took it at face value. One witness remembered how the students

and professors at Yale college "looked daily for the arrival

of the New York mail with unexampled avidity and implicit faith.

Have you seen the accounts of Sir John Herschel's wonderful discoveries?

Have you read the Sun? Have you heard the news of the man

in the Moon? These were the questions that met you every where.

It was the absorbing topic of the day. Nobody expressed or entertained

a doubt as to the truth of the story."

Despite this account, some competing newspapers

and sources at the time were skeptical about the series, expressing

doubt that the building of a new, fantastically-powerful telescope

- which would have taken years - would have gone without notice

in the English press. Interestingly enough, unlike other hoaxes,

the Sun never acknowledged the series was fiction, though

in its September 16th, 1835, edition, it did run a column discussing

such a possibility.

|

Ben

Franklin is thought to be the author of the Witch Trial

Hoax of 1730.

|

Witch

Trials in New Jersey

While profit and entertainment was often the reason

for such an article, sometimes a hoax story was also written to

make a political or social point. On October 22, 1730, The

Pennsylvania Gazette printed an article entitled A

Witch Trial at Mount Holly. The story, whose author is

thought to be Benjamin Franklin (who published the Gazette),

contains a description of a very unlikely witch trial in southern

New Jersey:

…the Accused had been charged with making their

Neighbours Sheep dance in an uncommon Manner, and with causing

Hogs to speak, and sing Psalms, &c. to the great Terror and Amazement

of the King's good and peaceable Subjects.

The authorities decided to try the witches (along

with two non-witches for comparison) by seeing if they weighed

less than a thick copy of the bible, or if they would float in

water - both thought to be ancients signs of a witch. When neither

test gave the inquisitors a reliable result, and believing that

the female accused's clothes might have helped her float, the

court decided to recess and try the water test again, later.

…they are to be tried again the next warm Weather,

naked.

Why did Franklin write this story? Probably he was

making a statement about the silliness of such beliefs. The Salem

witch trials had occurred just thirty-eight years before,

leading to the death of twenty-five people. The beliefs that led

to the trials were still prevalent in Franklin's day, and Franklin,

a man of science, wanted to expose such things as ludicrous.

Newspapers

More Than Just News

While some of these stories, like Franklin's, were

written to make people think, most were created to just amuse

the readership. The appearance of hoax stories in newspapers really

isn't that surprising if one recalls that much of the conventional

fiction of the day, which we now associate with books, was originally

published in the form of newspaper serials. Newspapers of the

era saw their role as entertaining the public as much as informing

it.

While the colorful tradition of hoax journalism

gives us an insight into entertainment in previous centuries,

it occasionally causes historians problems. Any strange tale found

in newspapers of the period must be considered suspect unless

it can be confirmed with other sources such as letters, other

publications, or physical evidence.

As the 19th century was left behind and the 20th

century dawned the public began to demand more accuracy from their

newspapers. Most dropped their hoax stories and many required

independent fact checking on important articles. A few tabloid

publications continued the hoax tradition, but with the demise

of The Weekly World News there is now one less. Still,

the Sun continues to be sold at newsstands and The Weekly

World News is available in a web edition, so just remember

when you see a headline like UFO CAPTURES LOCH NESS

MONSTER! that you're looking at the last of a long-standing

tradition.

Copyright Lee

Krystek 1996-2008. All Rights Reserved.