|

A

girl is forced to disrobe in a Salem Court so that she can

be checked for marks that would identify her as a witch.

From a painting by Thompkins H. Matteson.

|

Part I:

The Witches of Salem: The Events of 1692

Sometime toward the end of January, 1692, Betty

Parris, nine year-old daughter of the Reverend Samuel Parris,

became ill. She suffered from convulsions that contorted her body.

At times she would cry out and cower under chairs as if frightened

of something. Soon her thirteen-year-old orphaned cousin, Abigail,

who also lived in the Parris household, showed the same symptoms.

Reverend Parris and his wife did not recognize the malady and

had the girls examined by several doctors. The physicians could

find nothing wrong with the girls and by mid-February Dr. William

Griggs declared that he thought "the evil hand is upon them."

After that the word spread quickly through the tiny community

of Salem Village: "There are witches among us."

The events that took place in Salem, Massachusetts,

in 1692 are still shocking and controversial even today. Before

they were over, 19 people would be hung, four would die in jail,

and one would be tortured to death. In its wake the proceedings

would leave shattered families, suspicious neighbors and an embarrassment

to Massachusetts that the state government would still be apologizing

for three hundred years later. While the "why" of what

happened at Salem is still up for debate even today, the "what"

is fairly clear. In 1692 Salem was a small, somewhat poor, village

with a population of around 550 people. It lay just inland from

the much larger port of Salem Town and the residents were mostly

of the Puritan sect. These Protestants had left Europe and settled

in the new world hoping to be able to worship God as they pleased.

Ironically, even though they'd been forced to leave their homes

for religious reasons themselves, the Puritans tended to be very

intolerant of anybody else who broke their strict moral and legal

codes.

A Hard

Life

Life in Salem Village was grim. The winters were

cold and forbidding and good weather brought on the need for hard

work. Like any group of people living closely together, the Puritans

had their "haves" and "have nots" and disputes over land ownership

were frequent. The possibility of an outbreak of the deadly disease

smallpox was a constant concern. Some of the villagers were also

at odds with their spiritual leader, the Reverend Parris, who

was demanding a raise. Attacks by Native Americans had become

common among the towns of Massachusetts in the preceding years,

and this danger also played upon the villagers' minds. Finally,

and perhaps most foreboding of all, this was not the first time

the specter of witchcraft had raised its head in Salem Village.

Four years before a woman named Goody Glover had been accused

of witchcraft and hanged.

Over the following weeks, whatever was happening

to Betty and Abigail seemed to spread to other girls in the community.

To most observers their fits seemed beyond anything the girls

could have created themselves. The Reverend John Hale from a nearby

village wrote, " These children were bitten and pinched by invisible

agents; their arms, necks, and back turned this way and that way,

and returned back again, so as it was impossible for them to do

of themselves, and beyond the power of any epileptick fits, or

natural disease to effect."

Soon the "afflicted" in the village numbered seven,

ranging in age from nine to twenty. Betty, the youngest, was sent

away and spared what was to follow. The others continued to act

strangely and fears that they all were under a witch's evil spell

grew. Finally, one of the afflicted girl's aunt, Mary Stibley,

induced the Parris' family slave, Tituba, to bake a "witch cake"

to reveal the source of the evil. The cake, made of rye and the

girls' urine, was fed to the Parris's family dog, who Stibley

believed to be an evil messenger. The cake and the dog revealed

nothing, however, and earned Stibley a public rebuke from Rev.

Parris, who thought that using "white magic" to combat "black

magic" was unwise as he found all magic to be the tools of the

devil.

The

Accusations Begin

|

A

woman is hanged for witchcraft in Salem.

|

As the end of February approached, pressured mounted

on the girls to reveal the name of the witch or witches that tormented

them or somehow explain their bizarre behavior. Finally, seventeen-year-old

Elizabeth Hubbard named the Parris' slave, Tituba, as the witch.

Not much is known about Tituba other than she grew

up on the island of Barbados. She was likely of Native American

background, but nobody knows for sure. What is known is that during

the preceding winter months she kept some of the girls entertained

with stories of her native land with its strange traditions, games

and magic. In quick succession two other women were also named

as witches by the girls: Sarah Good and Sarah Osborn. The girls

claimed that the women "or specters in their shapes did grievously

torment them." Both the women were unpopular within the community:

Good smoked a pipe and was bad-tempered. Osborn did not attend

church and was entangled in a land dispute over her first husband's

will.

To be accused of witchcraft in those days was no

minor matter. In 1641 the English law had made the practice a

capital crime. It was thought that witches, who could be either

male or female, had made a pact with Satan agreeing to serve him

in return for certain powers which included the ability to curse

other people. Tituba, Good and Osborn were arrested on February

29th. The next day after questioning, which surely included a

beating, Tituba confessed "the devil came to me and bid me to

serve him." She also confirmed that Good and Osborn were her sister

witches. Her confession also made mention of a mysterious man

in black (perhaps the devil) and tales of flying through the air

on a broomstick.

Other accusations followed: Rebecca Nurse, Martha

Cory, Sarah Cloyce, and Elizabeth Proctor were arrested in March

and April. On April 11, John Proctor, husband of Elizabeth, became

the first man arrested for witchcraft after he protested the arrest

of his wife. Mary Warren, a maidservant of the Proctors and one

of the "afflicted" girls, recanted her accusations after her employers

were jailed saying that she and the other girls were lying. The

other girls immediately turned against Mary and accused her of

witchcraft. She quickly changed sides again saying that she was

lying about lying.

On May 27th the newly-elected governor, William

Phipps, commissioned the Court of Oyer and Terminer to try these

cases. The "afflicted girls" were star witnesses for the prosecution.

The court also allowed the use of "spectral evidence" which meant

that the girls could testify to seeing invisible entities that

nobody else could. The result of this was that no matter how wild

a story the girls made up, even though there was no way to corroborate

it with independent witnesses or evidence, it was still believed.

This would even play itself out in the middle of the courtroom.

If a defendant looked like that might win an acquittal, the girls

might suddenly start screaming and contorting their bodies as

if in pain. The girls would claim that the ghost, or "specter,"

of the defendant, which only the they could see, was attacking

them.

The

"Witches" are Put to Death

On June 2, 1692, Bridget Bishop became the first

person to be tried and convicted of witchcraft. Eight days later

she was hung on Gallows Hill. By July 19 there was a second round

of trials and convictions and five more women thought to be witches

were hung. More trials followed. August 19 saw five more hanged,

mostly men. John Proctor was among the group. His wife Elizabeth

only escaped the noose because she was pregnant.

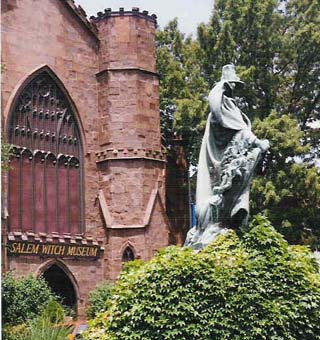

|

A

statue of a Puritan stands in front of the Witch Museum

in modern Salem town.

|

Before the trials were over, 141 people were arrested

for witchcraft. Ironically, only the honest people died. If one

was willing to confess to witchcraft they were forgiven. In fact,

not one person who actually confessed to witchcraft was hanged

or even brought to trial . This forgiveness came with a price,

however, as the accused were pressed to name other witches in

the community. While some people did this reluctantly, others

probably found it an excellent opportunity to settle old scores.

Sometimes this backfired, however. Giles Cory, who

earlier had refused to defend his wife when she was accused of

witchcraft, found himself under arrest as family members of witches

were looked at with considerable suspicion. Through a quirk of

law, a person could not be tried unless they submitted a plea

to the court. Giles Cory refused to do this, and to make him cooperate

sheriff's officers administered the Peine Forte Et Dure

to him. This torture consisted of putting the person under a large

wooden board and piling rocks on top of them until they said what

you wanted them to say. Giles Clory did not cooperate, however,

and after two days of being crushed, died.

The "afflicted girls," who for the most part were

servants, orphans and the weakest members of their society, suddenly

realized they had great power. They could strike fear into the

hearts of even the most powerful families in the village. Their

names were on everybody's lips as far away as Boston and they

were invited to other towns in the area to help expose witches.

More and more people were arrested and the hysteria spread through

Massachusetts.

An

End to the Madness

It is hard to say how long this would have continued

if the Governor's own wife had not been accused of witchcraft.

This prompted him to take control of the situation. On October

8th he ordered that spectral evidence no longer be allowed at

trials. At the end of the month he prohibited any more arrests,

released many of those in jail, and dissolved the court. Though

the hangings were over at that point, it still took until May

of 1693 before all those charged with witchcraft were either released

or pardoned.

What happened at Salem lay as an open wound in the

Massachusetts colony for many years. In 1697 the General Court

ordered a day of fasting and soul-searching for what had happened

at Salem. Samuel Sewall, who was one of the judges, publicly confessed

to his error and guilt in the fraudulent convictions. Nine years

later Ann Putnam Jr., one of the "afflicted girls," publicly apologized

for her part in the tragedy. The village of Salem, prompted by

the shadow of the trials, renamed itself to Danvers in 1752. Finally,

in 1957, the State of Massachusetts formally apologized for the

events of 1692.

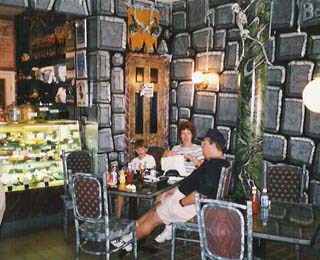

|

Visitors

can grab a bite to eat the the creepy Crypt Cafe.

|

Today the town of Salem revels in its connection

to the rather sordid history of the nearby village. Visitors can

go and visit a memorial dedicated to those that died or learn

about what happened from museums, historical plays or tours. They

can even have lunch at the Crypt Café which has an appropriately

creepy atmosphere.

The question that still haunts us today, however,

is why did it happen? What caused the girls to behave strangely

and accuse their neighbors? Almost none seriously believes that

witches were responsible. If Satan was not the source of this

tragedy, what was?

Part II: The Witches

of Salem: Theories and Speculations

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2006. All Rights Reserved.