|

A

woman is arrested for witchcraft in Salem. (Drawing by Howard

Pyle)

|

Part

II: The Witches of Salem: Theories and Speculations

In the year 1692 a number of young girls started

to show bizarre behaviors in the quiet village of Salem, Massachusetts.

They contorted and convulsed their bodies, crying out in an alarming

manner. Adults quickly concluded that the girls were bewitched

and hysteria swept through the small town. A court was convened

and 19 people, accused by these "afflicted" girls, were hung for

supposedly practicing witchcraft. Over a hundred other people

were arrested for the same crime and many spent months in jail.

A few died there.

What caused this sudden fear of witches and ripped

the small community apart? Nobody knows. The past three centuries,

however, have seen no end of books and articles filled with all

kinds of theories and speculation about the reasons behind the

terror. Today, scholars and pundits still look for meaning in

what happened. Here are some of the theories:

There

Really Were Witches at Salem

These days most people scoff at the idea that witches

exist, or if they do, that they have real supernatural powers.

It is important to remember, however, that in 1692 almost everybody,

from the most uneducated slave to the president of Harvard, believed

witchcraft was widely practiced and was a real threat to the community.

Cotton Mather, a respected Puritan minister who was present at

the time of the trials, wrote an account of them for the governor.

His essay clearly shows that he believed that some of the people

who were hung in Salem were indeed guilty of using black magic

to torment the "afflicted" girls. Though very much in the minority,

there are probably a few people even today who take the position

that this was indeed the case.

While many people in the period believed that witches

had supernatural powers given to them by the devil, many of the

better-educated people, such as philosopher Thomas Hobbes, acknowledged

that witchcraft was practiced but any spells that were cast only

had power in the minds of the witch and those that thought themselves

bewitched. It is important to note, however, that even Hobbes

thought that this kind of witchcraft, though it had no physical

power, brought real harm to a community and should be punished.

The

Afflicted Girls Thought They Were Being Bewitched

Here the argument is that in a society that believes

in witchcraft, witchcraft really works, not because there is any

supernatural power behind it, but simply because of how the fear

of being bewitched works on the victim's mind. Any symptoms such

as convulsive fits, blisters on the skin, or choking sensations

are psychosomatic rather than organic.

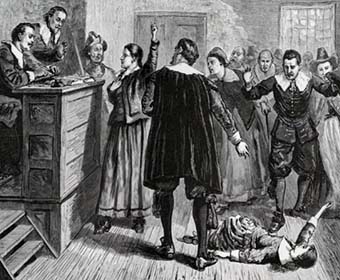

|

One

of the "afflicted" girls rolls on the ground as

a woman declares her innocence to the court.

|

Today we know that the mind can have a powerful

effect on the body. Placebos are a necessary part of many drug

studies in order that the psychological effects of taking the

medicine can be separated from the organic effects. Psychological

stress is known to cause all kinds of problems from rashes to

high-blood pressure and heart disease. Studies have shown that

hypnosis alone can induce an allergic reaction with no physical

agent involved.

If the girls believed that someone had cursed them,

that would have created enough stress in their minds to cause

physical symptoms. In fact, historian Chadwick Hansen argues that

many of the symptoms the girls had are nearly identical to a clinical

definition of hysteria.

Whether some of those accused of witchcraft actually

carried out some kind of ritual that might be associated with

cursing someone is not as important as if the girls believed that

this had been done. If the girls just believed that they had been

bewitched, it might have been enough to produce the physical effects

that were observed.

An

Out-of-Control Game

The "afflicted" girls who made the accusations

were some of the most powerless members of their society. Most

were young and unmarried, and some worked as menial servants for

other people. In the Puritan culture, nobody paid much attention

to them until they started acting strangely and having fits. Perhaps

it started as a game with the girls having no intentions of accusing

anyone of witchcraft or causing them harm. The concerned adults

around them seeking explanations soon came to believe the girls

were bewitched and started putting pressure on them to identify

the witch that was tormenting them. Perhaps the adults even suggested

a few candidates. Finally, when one of the girls gave in and named

a witch, they all saw what kind of power it gave them in the community

and how it would allow them to strike out at people they didn't

like.

Their fame wasn't only in the village but throughout

Massachusetts: a heady power trip for a young girl in Puritan

society. Once they started down this path, though, the girls found

themselves trapped. If they admitted that they had been lying,

they would be harshly punished for it, either by the authorities

or by the other girls.

At one point when it looked like someone was actually

going to be hung, one of the girls, Mary Warren, admitted she

had been making up the accusations and that the other girls had

been lying, too. Immediately, the rest of the girls turned on

her and identified Warren as a witch. Warren soon changed her

story again, saying she had been lying about lying. She had little

choice. If she had maintained that the girls had been making up

the stories about witches, she soon would have been tried as a

witch herself and probably hung. Many of the girls probably felt

like Warren that the game had gone too far but were unable to

confess to what they were doing for fear of what would happen

to them.

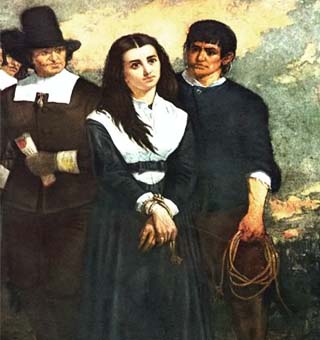

|

A

girl, terrified of being dragged off as a witch, seeks comfort

from a man, while her accuser and the village authorities

watch. From a painting by Douglas Volk.

|

There

was a Conspiracy Based on Village Politics

The village of Salem, even before the events of

1692, was considered one of New England's most divided communities.

Two extended families dominated the politics of the day: The Porters

and the Putnams. The issue that was on everyone's mind at the

time of the trials was whether the village of Salem should merge

with the town of Salem. The Porters favored this as they had close

connections with those in town and were already involved in town

politics. The Putnams did not, as they had exclusively focused

on village politics. The Putnams, while wealthy, were not as successful

as the Porters and were jealous. Perhaps they even blamed the

Porters and their friends for this.

One theory suggests that to get back at the Porters,

the Putnams had their girls accuse people in the community allied

with the Porters of being witches. There is some evidence for

this, as almost all the "afflicted" girls came from families connected

to the Putnams. The first two afflicted girls were Elizabeth Parris

and Abigail Williams, both members of Reverend Parris's household.

The Putnams were supporters of the Reverend Parris, the Porters

were against him. Ann Putnam, Jr, the daughter of Thomas Putnam,

was listed among the afflicted and apparently made many of the

accusations of witchcraft. Mercy Lewis, also an afflicted, worked

in his home. Mary Walcott, another accuser, was the step-daughter

of Deliverance Putnam, sister of Thomas.

The

"Afflicted" Girls Suffered from Some Physical Ailment

Some argue that the girls may have actually been

made sick by some unknown disease or poison that 17th century

medicine did not recognize. One of the causes most often mentioned

is ergot, a fungus found in rye grain. Ergot produces a poison

that affects the nervous and circulatory systems. Symptoms can

include convulsions, seizures and hallucinations.

Another possibility is that the girls contracted

encephalitis, a disease carried by mosquitoes. Encephalitis can

cause fever, headaches and confusion.

Critics of these explanations argue that it is unlikely

that only the girls in these households were affected by these

agents. However, if the agent was ergot, children and women seem

to be more susceptible to its poison and this may help explain

why only the girls seemed to be affected.

A Combination

of the Above Causes

|

A

woman is lead away to be hanged as a witch.

|

Perhaps the most likely explaination of what happened

is that it was a combination of many of the above possible causes.

It may be the case that the first victim, Beth Parris, may have

actually been sick with some unknown disease. It isn't hard to

imagine that the other girls, seeking the same attention she got,

joined in faking similar symtoms so they could share the limelight.

Adults, unable to find a satisfactory explaination in the natural

world, thought witchcraft was involved. The children were undoubtably

questioned about this. We know from recent studies that children

will try to please adults by giving them the type of answers they

seem to be seeking, especially if the the children are asked leading

questions or questioned repetitively. The adults would likely

ask the girls if the people tormenting them with witchcaft were

the people the adults considered in the community to be most-

likely allied with the devil: outcasts or political rivals. Some

of the girls, under this heavy questioning, might actually have

come to believe they were bewitched, while others knowingly lied

to please the adults and found themselves trapped in their own

lies.

We may never know for sure what were the exact causes

of the events in Salem Village in 1692. Sadly, these witchhunts

will probably be repeated in modern guise. One needs only to look

at the McCarty hearings of the 1950's and the satanic ritual abuse

trials of the 1980's to know that witchhunts are far from a thing

of the distant past.

Return

to Part I

A Partial Bibliography

The Salem Witch Trials, Edited by Laura Marvel, Greenhaven Press,

2003.

A Delusion of Satan, by Frances Hill, Da Capo Press, 2002.

The Devil in Massachusetts, by Marion L. Starkey, Doubleday,

1989.

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2006. All Rights Reserved.