pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Mystery Pit of Oak Island

One can only wonder what would have happened if young Daniel McGinnis had chosen to go exploring somewhere else on that fateful day in the summer of 1795. If he had, perhaps nobody else would have walked the woods on the eastern end of Oak Island for the next ten years. In that time, the clearing McGinnis found might have been reclaimed completely by the woods. In a forest, the thirteen foot-wide depression in the ground might never have been noticed. Thick, leafy branches might have obscured the old tackle block hanging from a branch directly over the pit. Without these markers, there would have been nothing to indicate that this was the work of man. And there might have never been the two-hundred year long treasure hunt that cost several fortunes and many lives. But McGinnis did see the clearing and the depression and the tackle block. Visions of pirate treasure did fill his head. He did return later with two friends, John Smith, age 19, and Anthony Vaughan, age 16. And together, with picks and shovels, they did start perhaps the most famous treasure hunt of modern times. Undoubtedly, the three must have thought they were on the verge of discovering the treasure of Captain William Kidd. Stories that the captain had buried a treasure hoard on an island "east of Boston" had been circulating since the 1600's. Legend had it that a dying sailor in the New England Colonies confessed to being a part of Kidd's notorious crew, but he never named an exact location for the hidden booty. The island McGinnis, Smith and Vaughan were on was one of 300 small isles in the Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada. It was peanut-shaped and about three-quarters of a mile long and 1,000 feet wide. Cutting away the smaller trees, the three young men started digging in the depression. After two feet they hit a floor of carefully laid flagstones. This type of slate was not found on the island and the group figured it had been brought there from about two miles north. Below the stones they saw that they were digging down a shaft that had been refilled. The walls of the shaft were scored with the marks of pick axes, more evidence that this structure was the work of men. At the ten foot level they hit wood. At first the group figured they'd hit a treasure chest, but quickly realized that they had found a platform of oaken logs sunk into the sides of the shaft. Pulling up the logs they discovered a two-foot depression and more of the shaft. Continuing to dig, they finally reached a depth of twenty-five feet. At that depth they decided they could not continue without more help and better planning. Covering the pit over, they left. One thing the three were sure of, though, was that something must be at the bottom of the pit. They concluded that nobody would have gone to the trouble of digging a shaft deeper than 25 feet unless he had something very valuable to hide. Nineteenth Century Excavations

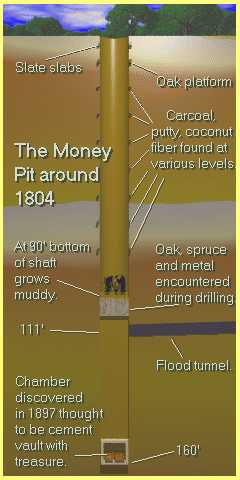

The work was started in the summer of 1803. After cleaning out the old pit, the crew started digging downward. Stories have it that they struck another oak platform at 30 feet below the surface. As they continued to dig they found something every ten feet: charcoal, putty, stones or more log platforms. Finally, at the 80 or 90 foot level, depending on which historical account you read, a flat stone, three feet long and one foot wide, with strange letters and figures cut into it, was found. At 93 feet deep, the floor of the pit began to turn into soft mud. Before the end of that day the crew probed the bottom of the shaft with a crowbar hoping to find something. They hit a barrier as wide and as long as the shaft. The group speculated that they'd finally reached the treasure vault and went to bed with the expectations that tomorrow a fortune would be theirs. Returning the next day, the crew was shocked to find that overnight the pit had filled with 60 feet of water. Bailing was useless. As soon as water was removed from the pit, more flowed in to take its place. An attempt was made to dig another shaft nearby and get at the treasure by running a tunnel underneath the pit, but the new shaft flooded as soon as the tunnel got close to its objective. Another attempt to find the treasure wasn't made until 1849. A new corporation was formed to finance the dig. This group wasn't much more successful, running into the same flooding problems that occurred back in 1802. They did manage to use a drill to probe what was below the money pit floor. A platform was constructed in the shaft just above the water level and the drill operated from there. The drill seemed to bore through levels of oak, spruce and clay. One sample recovered what appeared to be several links of chain made of gold. While the drilling was going on, someone noticed that the water in the pit was salty and rose and fell with the tide. This led to speculation that the builders of the pit had conceived a clever trap designed to flood the pit with water if someone got to close too the treasure. The existence of the flood trap was confirmed by the discovery that the beach of Smith's Cove, located some 500 feet away from the money pit, was artificial. Examination showed that the original clay of the cove had been dug away and in its place laid round beach stones, covered by four or five inches of dead eel grass, which was covered by coconut fiber two inches thick and finally the sand of the beach. At the bottom of all this were five box drains that apparently merged somewhere well back from the coast into a single tunnel that ran the distance to the money pit. The system was apparently designed so that the filtering action of the coconut fiber and the eel grass would ensure the drains would never be clogged by sand or gravel from the beach. It worked well. Attempts were made to put the flood trap out of business by building a cofferdam around the cove to by holding the tides back. Later, pits were dug to intersect and plug the tunnel on its route to the money pit. These failed, and this try at reaching the treasure was given up in 1851 when the money ran out. The next attempt in 1861 cost the first human life. The searchers tried to pump out the money pit using the steam engine-powered pumps. A boiler burst and one worker was scalded to death while others were injured. Further fatalities were barely avoided when the money pit's bottom, weakened by attempts to get at the treasure by digging up underneath from other shafts, collapsed. If there were any treasure chests they were probably carried much deeper by this crash. This dig did succeed in discovering where the flood tunnel entered the money pit, but there was still no way to turn off the water. By 1864 these searchers were also out of money. In 1866, 1893, 1909, 1931 and 1936 additional excavations were started. Extreme methods were used including setting dynamite charges to destroy the flood tunnel, building a dam to keep the water out of Smith's Cove, and bringing in a crane with an excavation bucket. None of these approaches recovered a single coin while costing the backers a small fortune and one worker his life. One of these efforts did manage to block off the flood tunnel from Smith's Cove, only to discover more water was pouring in from the opposite direction via a natural or man-made route from the south shore. Drilling also indicated that there might be some kind of cement vault at the 153-foot level. By this time the south end of the island was full of old shafts, though, and it was increasingly hard to tell were the original money pit was located. Searchers often ran out of money just trying to figure out where the old shaft had been. Modern ExcavationsIn 1959 Robert Restall, a former daredevil motorcyclist, took up the challenge with the help of his 18-year-old son. By then the Smith Cove's flood tunnel had become unblocked and Restall made it his first order of business to seal it off. He had sunk a shaft to the depth of 27 feet near Smith's Cove when tragedy struck. His son found him laying at the bottom of the pit in muddy water. Climbing down to help his father, the boy suddenly fell off the ladder and lay next to him. Kal Graseser, Restall's partner, and workers Cyril Hiltz and Andy DeMont climbed down to assist, but also collapsed before reaching the bottom. Edward White, a visiting fireman from Buffalo, New York, immediately suspected carbon monoxide poisoning from the exhaust of a nearby gasoline pump and descended the pit with a rope tied around his waist. He was able to rescue DeMont, but the others died. In one day Oak Island mystery claimed four more lives. In 1965 Robert Dunfield tried to apply modern open pit mining methods to the treasure hunt. Using a 70-ton digging crane he dug a hole at the original pit site 140 feet deep and 100 feet in diameter. The dirt was carefully sifted for any treasure, but only a few pieces of porcelain dishware were found. Heavy rains dragged the work out for months and Dunfield ran out of money. The pit, and its mystery designer, had won again.

In 1970 the Triton Alliance was formed to continue looking for the treasure. Legal battles between owners of different portions of the island resulted in slow progress. A number of holes were drilled in an attempt to locate the treasure and better understand the geological nature of the island, but no gold was recovered. Little work has been done in the area of the money pit itself as the soil is unstable. Often caverns, thought to be natural, have been found beneath the island. A video camera lowered down one borehole into one of these spaces recorded an image that looked like chests and a human hand severed at the wrist. The quality of the images was so poor, though, that positive identification was impossible. Triton brought the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in to survey the island in 1995 and render an opinion on whether there is something valuable at the bottom of the pit. While their report is confidential, people who have seen it say that its conclusions are "not discouraging." Currently little work is being done on the island while disputes between the owners of Triton are being settled. In addition to the money pit the rest of the island seems to be loaded with old stone markers of various types. The most peculiar of these are 6 boulders that seem to be laid out in the shape of a cross that is almost 900 feet long. Some wild speculation based on the cross suggest that Oak Island might be home to the long missing Holy Grail, but there is no real solid evidence to support this idea. Possible CulpritsSo, who built the money pit? And did they really put some kind of treasure down there? Was it Captain Kidd? Despite the legends it seem unlikely that Captain William Kidd ever had the chance to bury a treasure on Oak Island. He spent little time near Nova Scotia and certainly not enough to construct the money pit. Kidd did bury a cache of booty on Gardener's Island near the eastern end of Long Island Sound, but it was quickly seized by the Governor of New York. Blackbeard, who possessed perhaps the most notorious reputation of all pirates, has sometimes been mentioned in conjunction with Oak Island, but only because he once boasted he had an underground cache for his treasure, "where none but Satan and myself can find it." Certainly many of the Oak Island treasure hunters would agree that this sounds like the money pit, but the truth is there isn't any evidence that Blackbeard conducted any operations north of Delaware. In fact, it seems very unlikely that any pirate could be responsible for such a complex labyrinth as the pit. Pirates buried treasure because it offered a quick way to hide and recover their goods. A digging operation that must have taken several months just doesn't seem their style. George Bates, a land surveyor in Nova Scotia, suggested that pirates had indeed built structures on Oak Island, but not for the purpose of hiding treasure. Bate's idea was that there was enough pirate activity between 1650 and 1750 off the coast of Nova Scotia to warrant several pirate groups getting together and building a dry dock to maintain their ships. To do this they sailed their vessels into Smith's Cove and built a cofferdam to seal the tiny bay off from the ocean. The flood tunnel was used to then drain the cove and leave the ship high and dry. The water flooded down the tunnel into a large natural cave underneath the island. A windmill located on top of the money pit extracted the water so the cove could again be drained for the next ship.

Speaking of nature, is it possible that the money pit is a natural phenomena, not a cleverly designed vault? Certainly there are natural caves under Oak Island and the depression found by McGinnis could have been a sink hole. Unless all early accounts are completely incorrect the descriptions of the platforms carefully placed at 10-foot intervals seem to ensure that at least part of the structure is man-made. Some theories suggest that the structures built on Oak Island may have been hundreds, perhaps even thousand of years old when they were discovered in 1795. They may have been built by Vikings visiting the New World, or by the native Micmac people who lived in the region before the Europeans appeared. Perhaps they were built by an advanced civilization that we know nothing about. Indeed the flood tunnel trap built into the pit in some ways reminds one of the false doors and granite plugs found in Egyptian tombs to prevent grave robbing. If any of the above theories were true why did McGinnis discover the pit in the heart of a clearing? The trees around the money pit must have been cut when it was constructed. Given the rate oak trees grow, that meant someone had built the pit not more than fifty years before McGinnis stumbled across it. Who would have hidden a treasure between 1745 and 1795? William Crooker, author of several books on the Oak Island mystery, suggests that the pit was built as a part of plot by King George III of England and several of his close advisors. On August 12, 1762, British forces captured the city of Havana, Cuba, from the Spanish. Havana was a rich, important city where much of the gold from the New World was shipped back to Spain. Two shiploads of the captured booty, Crooker suggests, was taken by the Earl of Albemarle to Oak Island. Previously the conspirators had arranged for military engineers to come to the island and build what they thought was a secret ammo dump complete with flood tunnels. Albemarle arrived with the treasure in sealed boxes. The treasure was placed in the pit, the pit was closed, and the engineers departed still thinking they had built an ammo dump. Albemarle returned to England with the idea of retrieving the treasure later. Something, perhaps the madness that afflicted King George toward the end of his life, prevented getting the booty and it was forgotten about. Crooker's theory raises another possibility, though. Suppose there is no treasure at all and the pit is simply an old ammo dump? We will only find out for sure when someone comes along who is clever enough, and rich enough, to beat the designer of the money pit and make a thorough investigation of what lies at the bottom.

Copyright Lee Krystek 1998. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|

Not

much more was done with the pit until around 1802. While stories

differ, it seems likely that the three spent the previous years

searching for a financial backer to provide assistance for a

more sophisticated dig. Simeon Lynds visited the money pit that

year, was impressed by the story, and formed a company to support

the excavation.

Not

much more was done with the pit until around 1802. While stories

differ, it seems likely that the three spent the previous years

searching for a financial backer to provide assistance for a

more sophisticated dig. Simeon Lynds visited the money pit that

year, was impressed by the story, and formed a company to support

the excavation.

The

weakness of Bates argument is that located on the other side of

Nova Scotia, only a hundred miles away, is the Bay of Fundy. The

tides in the bay drop at least 30 feet each day making it a huge

natural dry dock. Why would the pirates duplicate what nature

already provided?

The

weakness of Bates argument is that located on the other side of

Nova Scotia, only a hundred miles away, is the Bay of Fundy. The

tides in the bay drop at least 30 feet each day making it a huge

natural dry dock. Why would the pirates duplicate what nature

already provided?